In 2017, I spoke with a music historian to understand the trend of flute rap: a boom in rappers rhyming about codeine, cars, and trauma over the soft sound of breath moving through a tube. Ardal Powell, the author of The Flute, told me that nothing surprised him when it came to this instrument. It is possibly the oldest musical device in the world. Neanderthals and 15th-century Swiss mercenaries and 1970s heavy-metal bands found use for it. Why not rappers?

The “key thing in the history of the flute, going back thousands of years,” Powell said, is that “it’s the closest instrument to the human voice.” No reed or mouthpiece separates the player’s breath from the sound it makes. This observation suggested that the flute, all along, was a bit hip-hop. And at its best, rap can seem like an act of inner channeling, of making the body and mind one. The flute is difficult to master but, fundamentally, intuitive to operate—intuitive like tapping out a rhythm, or like speaking.

André 3000’s intuition long ago earned him a claim to being one of the greatest rappers alive. Starting in the early 1990s as half of the Atlanta group Outkast, he specialized in wise and funny verses connecting street life with the stars. He was in conversation with his peers in southern rap—known for lackadaisical charm and sonic-boom bass lines—but also with Prince, Shakespeare, and Carl Sagan. Eventually, however, his vision dimmed. Outkast’s last album was released in 2006, and since then, André has put out almost no solo music. The reason for his silence, he has said, was lack of inspiration. Life in middle age wasn’t sparking new bars.

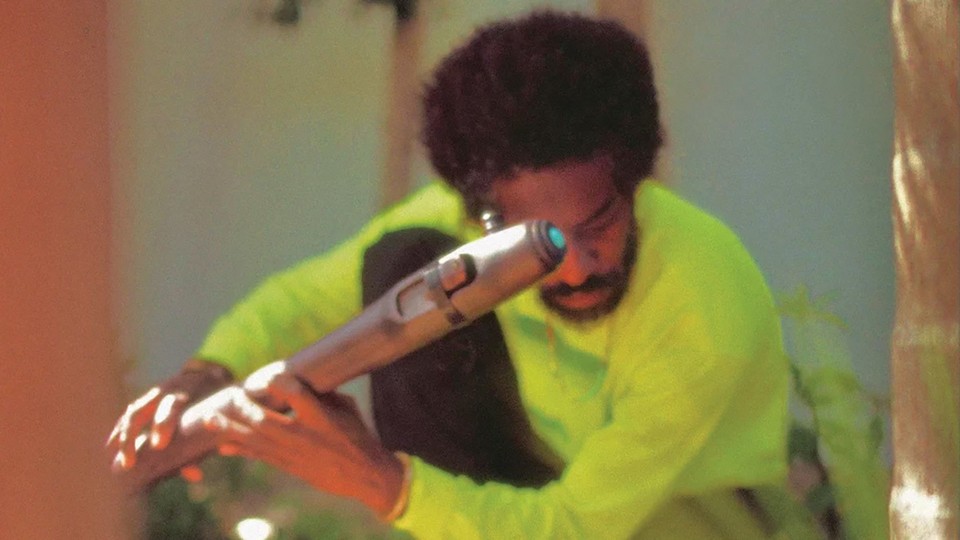

Now he’s back with a new album, and he’s speaking in a new voice, or rather rendering his voice in a new guise with the flute. Over the past half decade or so, André collected reedless woodwinds from around the world; playing the flute, he has said, is a better way of passing time than scrolling through a smartphone. He loved that the instrument made him, a master of one art form, into a “baby” at another, he told GQ. Returned to newbie status, his creativity flared once again. These days, he’d feel uncomfortable if someone were to ask him to freestyle rap. But he’d happily improvise on the flute.

New Blue Sun, his first album in 17 years, features no rapping and lots of flute. It also has drums, keys, guitars, and other instruments, played by well-respected improvisatory musicians led by the percussionist Carlos Niño, whom André befriended at a crunchy Los Angeles grocery store. For hip-hop fans who’ve long awaited his return, disappointment is inevitable; the opening track title even apologizes: “I Swear, I Really Wanted to Make a ‘Rap’ Album but This Is Literally the Way the Wind Blew Me This Time.” (His aesthetic compass told him to write song names that long, and mine is telling me to abbreviate them for the rest of this article.) Charitably, the project seemed at first to signal retirement boredom, a retreat from ambition. Signs pointed to it sounding like kitsch jazz or spa music, like comedy or wallpaper.

But it turns out the album is stranger than that. I first listened to New Blue Sun while doing chores, and it really got on my nerves. The flute playing sounds rudimentary and halting, the sound of someone practicing aimlessly rather than committing to an idea. The rest of the band drowns André out with smoggy synthesizer chords and percussion that rustles with the irregularity of an animal climbing in a bush. (“Plants” are listed in the instrumental credits.) I am not much of a jazz listener, but I know enough of John and Alice Coltrane—two stated influences—to know that the pulsing ferocity of those cosmic greats isn’t present. Nor does the album achieve Brian Eno-ian usefulness, melding into my life.

But later, as I lay awake in a dark room, the music clicked. A pleasant coldness settled into my body three tracks in, on “That Night in Hawaii When I Turned Into a Panther … ,” whose minimal drum thump calls to mind an Ennio Morricone soundtrack, foreboding and lonely. Midway through the song, André locks into a melody that wheels up and up, and I felt carried with it. The next track, “BuyPoloDisorder’s Daughter … ,” seems to open up onto a cloudscape, with tufts of keyboard that billow and shiver. A sunray of a synthesizer erupts about eight minutes in, cohering the song’s mood, adding warmth. It’s like the moment a pot of ingredients, stirred and simmered at great length, finally thickens into a sauce.

Dissecting instrumental music requires either using technical terminology—which most people, André included, do not think in—or writing in the fairly silly way I did in the previous paragraph: mixing metaphors in an attempt to render subjective sensations concretely. It is very easy, when communicating in this mode, to rhapsodize past the point of meaning anything at all. One must be sure to draw contrasts, saying what something is like but also what it is not. (As a rapper, André always knew this; he’d take time in a verse to delineate the difference between slumber party and spend the night.)

So: Listening to New Blue Sun is not like listening to rap, watching a movie, or staring at a painting. It’s more like looking out of a wide window on a changing and interesting scene. The individual sounds remind me of bubbles—crowding, dilating, and suddenly dissipating. The overall songs move cyclically (breathe in, breathe out) but not repetitively (each breath is different from the last). Most important: The album’s best passages—the prismatic goo of “Ghandi, Dalai Lama …”; the subtle, drifting “Dreams Once Buried …”—are beautiful in original ways. They create shapes you’ll find nowhere else.

People will no doubt play this album to help them empty their brain for sleep or to congeal a vibe during dinner parties. But I’m not sure these are the best uses of it. Maybe if André were removed, New Blue Sun would fit more stereotypical notions of ambient or new-age music. But his flute, blowing humbly yet insistently within the canyon of reverberation created by the more veteran instrumentalists, sounds too alive—and flawed—to tune out. He’s not the virtuosic soloist or the hypnotizing pied piper; he’s more like someone talking to himself on a hike. I personally cannot write or even think when music with lyrics is playing in my ears, and the flute of New Blue Sun nearly achieves the same distracting effect. You hear intelligence at work; you hear language without words.

This is, strange as it is to say, music to listen to. André recently told NPR that playing the flute isn’t a “set-out meditation,” and emphasized, “I have to force myself to pay attention to what I’m doing.” For the listener of New Blue Sun, the same imperative holds. Spotify and its kind have flooded the music ecosystem with cheap background noise. This album is a reminder of the rewards that can come with taking time to tune in rather than tune out.

In that same NPR interview, André said that his flute melodies flowed out of thoughts that he feels unwilling or unable to put into words. Music, he said, is “sub-talk,” encoding ideas that different people will translate in different ways. Some fans will try to solve these songs like a puzzle (hoping to find the release date for an actual rap album, one imagines). But to approach this album as though it contains a hidden message isn’t quite right. The point of New Blue Sun, as with so much great music, is the inarticulable narrative created by the changing relationship between sounds. A tale lies, too, in the album’s status as an act of lively creation for someone who felt burnt out by words. In his way, André is still pursuing the art of storytelling.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.