VOL. 12, No. 3 - lankesteriana.org

VOL. 12, No. 3 - lankesteriana.org

VOL. 12, No. 3 - lankesteriana.org

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

ISSN 1409-3871<br />

<strong>VOL</strong>. <strong>12</strong>, <strong>No</strong>. 3 December, 20<strong>12</strong><br />

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL ON ORCHIDOLOGY

The Vice-Presidency of Research<br />

University of Costa riCa<br />

is sincerely acknowledged for his support<br />

to the printing of this volume

ISSN 1409-3871<br />

<strong>VOL</strong>. <strong>12</strong>, <strong>No</strong>. 3 DECEMBER 20<strong>12</strong><br />

A new and extraordinary Cyrtochilum (Orchidaceae: Oncidiinae)<br />

from Colombia<br />

Giovanny Giraldo and StiG dalStröm<br />

A new Cyrtochilum (Orchidaceae: Oncidiinae) from Sierra Nevada<br />

de Santa Marta in Colombia<br />

StiG dalStröm<br />

Three new small-flowered Cyrtochilum species (Orchidaceae: Oncidiinae)<br />

from Colombia and Peru, and one new combination<br />

StiG dalStröm and Saul ruiz Pérez<br />

A well-known but previously misidentified Odontoglossum<br />

(Orchidaceae: Oncidiinae) from Ecuador<br />

StiG dalStröm<br />

Ponthieva hermiliae, a new species of Orchidaceae in the Cordillera<br />

Yanachaga (Oxapampa, Pasco, Peru)<br />

luiS valenzuela Gamarra<br />

Species differentiation of slipper orchids using color image analysis<br />

erneSto Sanz, noreen von Cramon-taubadel and david l. robertS<br />

Estudio de la orquideoflora de la reserva privada Chicacnab,<br />

Alta Verapaz, Guatemala<br />

edGar alfredo mó mó y edGar armando ruiz Cruz<br />

Index of nex taxa and combinations published in Lankesteriana,<br />

vol. 10–<strong>12</strong> (2010–20<strong>12</strong>)<br />

Reviewers of the manuscripts submitted to Lankesteriana, vol. 10–<strong>12</strong><br />

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL ON ORCHIDOLOGY<br />

137<br />

143<br />

147<br />

155<br />

161<br />

165<br />

175<br />

191<br />

193

InternatIonal Journal on orchIdology<br />

Copyright © 20<strong>12</strong> Lankester Botanical Garden, University of Costa Rica<br />

Effective publication date: December 28, 20<strong>12</strong><br />

Layout: Jardín Botánico Lankester.<br />

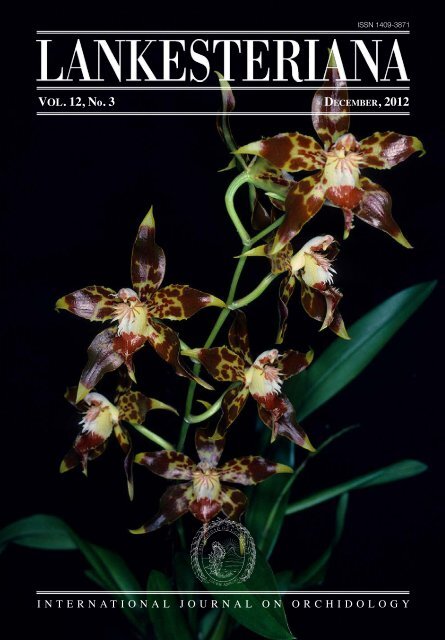

Cover: Odontoglossum furcatum Dalström (Ecuador. A. Hirtz 368). Photograph by S. Dalström.<br />

Printer: MasterLitho<br />

Printed copies: 500<br />

Printed in Costa Rica / Impreso en Costa Rica<br />

R Lankesteriana / International Journal on Orchidology<br />

<strong>No</strong>. 1 (2001)-- . -- San José, Costa Rica: Editorial<br />

Universidad de Costa Rica, 2001-v.<br />

ISSN-1409-3871<br />

1. Botánica - Publicaciones periódicas, 2. Publicaciones<br />

periódicas costarricenses

Visit the new webpage at<br />

www.<strong>lankesteriana</strong>.<strong>org</strong><br />

Originally devoted to the publication of articles on general botany, with special attention to epiphytic<br />

plants and orchid systematics, ecology, evolution and physiology, along with book reviews and conferences<br />

on these subjects, since 2007 lankeSteriana focused exclusively on scientific papers on orchidology.<br />

lankeSteriana is a peer-reviewed journal that publishes original works in English and occasionally in Spanish,<br />

and it is distributed to more than 350 libraries and institutions worldwide.<br />

lankeSteriana is indexed by BioSiS, Latindex, Scirus, and Wzb, it is included in the databases of E-journals,<br />

Ebookbrowse, Fao Online Catalogues, CiteBank, Mendeley, WorldCat, Core Electronic Journals Library, and<br />

Biodiveristy Heritage Library, and in the electronic resources of the Columbia University, the University of<br />

Florida, the University of Hamburg, and the Smithsonian Institution, among others.<br />

In order to increase visibility of the articles published in lankeSteriana, the journal maintains since 2009 a web<br />

page with downloadable contents. Since <strong>No</strong>vember, 2011, the journal has a new and improved interface of at<br />

www.<strong>lankesteriana</strong>.<strong>org</strong>. Please bookmark the new address of the webpage, which substitutes the previous address<br />

hosted at the internal server of ucr.ac.cr.<br />

Readers can now browse through all the past issues of lankeSteriana, including the currrent issue, and<br />

download them as complete fascicles or, via the Index to the single issues, only the articles of their interest.<br />

According to the Open Access policy promoted by the University of Costa Rica, all the publications supported<br />

by the University are licensed under the Creative Commons copyright. Downloading lankeSteriana is completely<br />

free. At the home page of lankeSteriana you may also search for author names, article titles, scientific<br />

names, key words or any other word which should appear in the text you are looking for.<br />

We acknowledge our authors, reviewers and readers, who help us making a better scientific journal.<br />

The editors

The Global Orchid Taxonomic Network at a click<br />

www.epidendra.<strong>org</strong><br />

<strong>No</strong>w with a new user interface, the online database on taxonomic information by Lankester Botanical Garden<br />

includes more than 7,000 orchid names, completely cross-referenced and with evaluated synonymies.<br />

The electronic file on each one of the names accepted by the taxonomists at the research center includes free, immediately<br />

downloadable protologues, type images, illustrations of the original materials, historical and modern<br />

illustrations, photographs, pertinent literature and, when available, digital images of species pollinaria.<br />

An index (under the button “List of species”) allows the users to search for any published name, independently<br />

if it is accepted or not by the taxonomic compilers. Synonyms are linked to their accepted name,<br />

where additional materials (including images) are available for download.<br />

Hundreds of new species names and documents (mostly protologues), images (including high-res files), publications<br />

and other materials relative to orchid systematics, distribution and history are added to the database on<br />

a monthly basis (new entries can be searched by clicking on the “New records” button).<br />

Since March, 20<strong>12</strong>, new pages are devoted to the orchid species recorded in the rich system of national parks<br />

and other protected areas in Costa Rica (“National Parks” button), updated checklists of the orchid floras of<br />

Central American countries (“Floras” button) and to interesting aspects of orchid history.<br />

Under the button “Collectable plates”, the research staff at Lankester Botanical Garden makes available to the<br />

public the most detailed images of orchids from the collections at the Center, <strong>org</strong>anized in a series of collectable<br />

plates that can be downloaded for free. New ones are added each week.<br />

Supported by the University of Costa Rica and the Darwin Initiative, EpidEndra, The Global Orchid Taxonomic<br />

Network counts with the collaboration of respected taxonomists and leading botanical institutions worldwide.

LANKESTERIANA <strong>12</strong>(3): 137—142. 20<strong>12</strong>.<br />

A NEW AND EXTRAORDINARY CYRTOCHILUM (ORCHIDACEAE:<br />

ONCIDIINAE) FROM COLOMBIA<br />

Giovanny Giraldo 1 & StiG dalStröm 2,3<br />

1 Department of Botany, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 430 Lincoln Drive,<br />

Madison WI 53706-1381, U.S.A.<br />

2 2304 Ringling Boulevard, unit 119, Sarasota FL 34237, U.S.A.<br />

Lankester Botanical Garden, University of Costa Rica, Cartago, Costa Rica<br />

and National Biodiversity Centre, Serbithang, Bhutan<br />

3 Corresponding author: stigdalstrom@juno.com<br />

abStraCt. A new species of Cyrtochilum from Antioquia, Colombia, is described and illustrated, and compared<br />

with the similar Ecuadorian C. cryptocopis and C. trifurcatum, but differs in having a different ventral structure<br />

and much narrower wings of the column, and also by the much broader frontlobe of the lip.<br />

key wordS: Cyrtochilum, Colombia, Oncidiinae, new species, taxonomy<br />

Despite two centuries of intense hunting for orchids<br />

in the Colombian wilderness, as well as extensive<br />

deforestation and urbanization, new and extraordinary<br />

species are found rather frequently. New and attractive<br />

species of Phragmipedium Rolfe have recently been<br />

described, and large numbers of showy pleurothallids<br />

in genera such as Dracula Luer, and Masdevallia Ruiz<br />

& Pav., as well as a plethora of other types of orchids<br />

never seem to stop appearing in the botanical literature.<br />

This paper describes a new Cyrtochilum Kunth, from<br />

the western cordillera where it was initially discovered<br />

by one of the authors (GG) as his attention was caught<br />

by the dancing brown and yellow flowers on the long<br />

pendant inflorescence while walking through the<br />

national preserve.<br />

Cyrtochilum betancurii G.Giraldo & Dalström sp.<br />

nov.<br />

TYPE: Colombia, Antioquia, Mun. Urrao. Parque<br />

Nacional Natural las Orquídeas, in cloud forest at<br />

1600-1800 m elevation. February 2, 2011. J. Betancur<br />

14882 (holotype, COL). Fig. 1—3.<br />

diaGnoSiS: Cyrtochilum betancurii is most similar to<br />

the Ecuadorian C. cryptocopis (Rchb.f.) Kraenzl. (Fig.<br />

4), and C. trifurcatum (Lindl.) Kraenzl. (Fig. 5), but<br />

has a different ventral structure and much narrower<br />

wings of the column, and also by the much broader<br />

frontlobe of the lip.<br />

Epiphytic herb. Pseudobulbs distant on a<br />

creeping, bracteate rhizome, oblong ovoid and slightly<br />

compressed, ca. 4.3 × 2.1 cm, unifoliate or bifoliate,<br />

surrounded basally by four to six distichous foliaceous<br />

sheaths. Leaves subpetiolate, conduplicate, obovate,<br />

acute, to ca. 40.0–50.0 × 5.0–6.0 cm. Inflorescence<br />

axillary from the uppermost sheath, erect then wiry,<br />

straight to loosely flexuous to ca. 2.80 m long panicle,<br />

with a basal longer branch, and then several widely<br />

spaced, short, few-flowered side-branches, carrying<br />

in total 16 to 18 flowers (although larger specimens<br />

with more flowers are likely to exist). Floral bracts<br />

appressed, scale like, ca. 1.0 × 0.6–0.7 cm. Pedicel<br />

with ovary ca. 4.5 cm long. Flowers stellate and showy;<br />

dorsal sepal dark brown with yellow border, basally<br />

auriculate, spathulate, broadly cordate, distinctly<br />

undulate, obtuse to acute and slightly oblique, 3.6 ×<br />

2.4 cm; lateral sepals dark brown, basally auriculate<br />

and connate for 6.0–8.0 mm, then spreading, elongate<br />

and narrowly spathulate, then cordate, slightly<br />

undulate, obtuse to rounded and slightly oblique, ca.<br />

7.4 × 2.3 cm; petals dark brown with a yellow border,<br />

broadly linear and shortly spathulate, then truncate<br />

to cordate, distinctly undulate, obtuse to acute and<br />

slightly oblique, ca. 2.5 × 1.8 cm; lip dark brown with<br />

yellow border and callus, rigidly attached to the base<br />

of the column through a narrow and terete claw, then<br />

truncate, distinctly pandurate with spreading, slightly<br />

oblique, broadly auriculate, slightly serrate lateral

138 LANKESTERIANA<br />

fiGure 1. Cyrtochilum betancurii. A. Plant habit. B. Flower, front view. C. Lip, ventral view. D. Column and lip, lateral<br />

view. E. Flower dissected. Drawn from holotype by Sarah Friedrich.<br />

lobes, and a ca. 4 mm broad isthmus below the widely<br />

spreading and broadly dolabriform, obtuse to acute,<br />

emarginate, revolute frontlobe, 1.8 × 1.8 cm; callus<br />

complex and fleshy, emerging near the base of the<br />

lateral lobes and extending for ca. 5 mm, consisting<br />

of an erect, table-like, tricarinate structure with several<br />

lateral, spreading denticles, with additional series of<br />

spreading tubercles or denticles on each side, and an<br />

LANKESTERIANA <strong>12</strong>(3), December 20<strong>12</strong>. © Universidad de Costa Rica, 20<strong>12</strong>.<br />

apical, central, longitudinal and triangular keel, with<br />

spreading, dorsally flattened, fleshy, lateral keels;<br />

column purplish brown, stout, erect in a ca. 90° angle<br />

from the base of the lip then slightly curved towards<br />

the lip near the apex, with a complex, protruding,<br />

terete, trilobate concavity on the ventral side below<br />

the stigma, and with a pair of clavate to obliquely and<br />

narrowly deltoid, or bilobed, spreading blackish purple

Giraldo and dalStröm — A new Cyrtochilum from Colombia 139<br />

A B<br />

fiGure 2. Cyrtochilum betancurii, flower in frontal (A) and lateral (B) views. Photo by G. Giraldo.<br />

fiGure 3. Cyrtochilum betancurii, detail of the column and<br />

lip, lateral view. Photo by G. Giraldo.<br />

wings on each side below the stigma; anthercap yellow<br />

and purplish, campanulate; pollinarium not seen.<br />

diStribution: Colombia, Antioquia, Mun. Urrao.<br />

Parque Nacional Natural las Orquídeas on the western<br />

cordillera.<br />

ePonymy: Named in honor of Julio Betancur, leader<br />

of the expedition to Parque Nacional Las Orquideas,<br />

and a renowned Colombian botanist with great<br />

experience and passion for tropical plants that has<br />

positively influenced a new generation of Colombian<br />

botanists.<br />

Cyrtochilum betancurii is only known from the<br />

type collection in the cloud forests of the western<br />

cordillera in Colombia. Because of its restricted<br />

location the authors recommend its protection until<br />

LANKESTERIANA <strong>12</strong>(3), December 20<strong>12</strong>. © Universidad de Costa Rica, 20<strong>12</strong>.

140 LANKESTERIANA<br />

fiGure 4. Cyrtochilum cryptocopis. A. Column and lip, lateral view. B. Column, lateral and frontal views. C. Column, ventral<br />

view. D. Anther cap and pollinarium. E. Lip, spread. F. Flower dissected. Drawn from Dalström 2800 (SEL) by Stig Dalström.<br />

LANKESTERIANA <strong>12</strong>(3), December 20<strong>12</strong>. © Universidad de Costa Rica, 20<strong>12</strong>.

Giraldo and dalStröm — A new Cyrtochilum from Colombia 141<br />

fiGure 5. Cyrtochilum trifurcatum. A. Column and lip lateral view. B. Column lateral view. C. Column ventral view. D.<br />

Anther cap and pollinarium. E. Lip, spread. F. Flower dissected. Drawn from Dodson 14034 (SEL) by Stig Dalström.<br />

LANKESTERIANA <strong>12</strong>(3), December 20<strong>12</strong>. © Universidad de Costa Rica, 20<strong>12</strong>.

142 LANKESTERIANA<br />

more information about the species distribution can be<br />

gathered.<br />

aCknowledGmentS. The authors wish to thank the NSF<br />

funded project; Flora of Las Orquideas National Park (DEB<br />

1020623 to Pedraza), for funding the fieldwork and making<br />

specimens available, and also the New York Botanical<br />

Garden, Universidad Nacional de Colombia and Unidad<br />

de Parques Nacionales Naturales de Colombia. In addition<br />

we especially thank Hector Velásquez and the park rangers<br />

for assisting in the logistics and successfully executing the<br />

field trip. We are very thankful to Sarah Friedrich, Media<br />

Specialist in the botany department at UW-Madison for<br />

LANKESTERIANA <strong>12</strong>(3), December 20<strong>12</strong>. © Universidad de Costa Rica, 20<strong>12</strong>.<br />

the preparation of the type illustration. The first author also<br />

thanks the botanists Julio Betancur, Paola Pedraza, Maríaa<br />

Fernanda González, and the photographer Fredy Gómez<br />

for their company and support, making the field trip an<br />

unf<strong>org</strong>ettable and enriching experience.<br />

literature Cited<br />

Dalström, S. 2010. Cyrtochilum Kunth, in Flora of Ecuador<br />

225(3): Orchidaceae; genera Cyrtochiloides–Epibator,<br />

by Calaway H. Dodson and Carl A. Luer. Department<br />

of Plant and Environmental Sciences, University of<br />

Gothenburg, Sweden.

LANKESTERIANA <strong>12</strong>(3): 143—145. 20<strong>12</strong>.<br />

A NEW CYRTOCHILUM (ORCHIDACEAE: ONCIDIINAE) FROM SIERRA<br />

NEVADA DE SANTA MARTA IN COLOMBIA<br />

StiG dalStröm<br />

2304 Ringling Boulevard, unit 119, Sarasota FL 34237, U.S.A.<br />

Lankester Botanical Garden, University of Costa Rica, Cartago, Costa Rica<br />

and National Biodiversity Centre, Serbithang, Bhutan<br />

stigdalstrom@juno.com<br />

abStraCt. A new species of Cyrtochilum from the isolated region of Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta in Colombia<br />

is described and illustrated, and compared with similar species. It is distinguished from other Cyrtochilum<br />

species by the violet color of the sepals and petals, in combination with the pandurate lip lamina with a large<br />

and protruding nose-like central callus keel.<br />

key wordS: Cyrtochilum, Orchidaceae, Oncidiinae, new species, Colombia, Santa Marta, Sierra Nevada,<br />

taxonomy<br />

During a past visit to the Marie Selby Botanical<br />

Gardens (MSBG) in Sarasota, Florida, Mariano Ospina<br />

brought a large number of dried orchid specimens for<br />

identification purposes, mainly from the National<br />

Herbarium of Colombia (COL) in Bogotá. The<br />

herbarium batch consisted of species that today are<br />

placed in many different genera, including Cyrtochilum<br />

Kunth, Erycina Lindl., Heteranthocidium Szlach.,<br />

Mytnik & Romowicz, Oncidium Sw., Otoglossum<br />

(Schltr.) Garay & Dunst., and Trichocentrum Poepp.<br />

& Endl. (the names of the genera vary depending on<br />

which taxonomist is consulted). During this project,<br />

which was a collaboration between Ospina and<br />

MSBG, I had the opportunity to analyze the material<br />

and encountered a Cyrtochilum species that was<br />

unknown to me. A drawing was made at the time of<br />

this unusual looking and most certainly quite attractive<br />

species. Eventually it became clear that it represented<br />

an undescribed species, which is described herein.<br />

Cyrtochilum violaceum Dalström, sp. nov.<br />

TYPE: Colombia, Magdalena, Sierra Nevada de Sta.<br />

Marta, Transecto del Alto Rio Buritaca, Cuchilla at<br />

2900 m, Lev. 29. Proyecto Desarrollo, 5 August 1977;<br />

R. Jaramillo M. et al. 5366 (holotype, COL). fiG. 1.<br />

diaGnoSiS: Cyrtochilum violaceum is distinguished<br />

from other Cyrtochilum species by the violet color of<br />

the sepals and petals, in combination with a pandurate<br />

lip lamina with a large and protruding nose-like central<br />

callus keel, which is similar to the not closely related<br />

Oncidium mantense Dodson & R.Estrada. Cyrtochilum<br />

violaceum differs from the similarly colored and<br />

closely related Cyrtochilum undulatum Kunth [syn: C.<br />

<strong>org</strong>yale (Rchb.f. & Warsc.) Kraenzl.] by the pandurate<br />

lip lamina, the cleft and distinct frontal angles of the<br />

stout column, and the pair of digitate or narrowly<br />

clavate wings on each side below the stigmatic surface,<br />

versus a triangular lip lamina, and a more slender and<br />

sigmoid column of the latter species with short angular<br />

knobs only, or without wings altogether.<br />

Epiphytic herb. Pseudobulbs caespitose to<br />

creeping on a bracteate rhizome, ovoid, ca. 5 × 2<br />

cm, bifoliate, surrounded basally by 7 to 8 distichous<br />

sheaths, the uppermost foliaceous. Leaves subpetiolate,<br />

conduplicate, elliptic to slightly obovate, narrowly<br />

acute, ca. 16–17 × 2 cm. Inflorescence axillary from<br />

the uppermost sheath, an erect to arching, to ca. 70<br />

cm long loosely flexuous panicle, with widely spaced<br />

3 to 4 flexuous, 2– to 4–flowered side-branches (up<br />

to 6 or more flowers on 7 branches have been noted<br />

on an additional specimen). Floral bracts large and<br />

conspicous, involute and cucullate, ca. 10–15 mm<br />

long. Pedicel with ovary 20–25 mm long. Flowers<br />

apparently open and stellate; dorsal sepal violet,<br />

shortly spathulate, then truncate and broadly ovate<br />

to elliptic laminate, obtuse, slightly undulate, ca.

144 LANKESTERIANA<br />

fiGure 1. Cyrtochilum violaceum. A. Plant habit. B. Column and lip lateral view. C. Lip dorsal view. D. Column lateral view.<br />

E. Pollinia and stipe. F. Flower dissected. Drawn from holotype by Stig Dalström.<br />

LANKESTERIANA <strong>12</strong>(3), December 20<strong>12</strong>. © Universidad de Costa Rica, 20<strong>12</strong>.

25 × 18 mm; lateral sepals similar in color, slightly<br />

obliquely spathulate, then obliquely cordate, broadly<br />

and weakly pandurate laminate, obtuse, ca. 25 × 15<br />

mm; petals similar in color, almost sessile, truncate to<br />

cordate, then broadly ovate and rounded obtuse with<br />

a canaliculate acute, almost folded apex, ca. 20 × 13<br />

mm; lip rigidly attached to the base of the column<br />

and angled downwards, truncate to cordate, pandurate<br />

with obtuse triangular lateral lobes, and a rounded<br />

and slightly concave, weakly bilobed to minutely<br />

apiculate frontlobe, ca. 10 × 8 mm; callus yellow, of<br />

a fleshy denticulate structure emerging from the base<br />

and extending to almost half the length of the lamina,<br />

with several spreading lower lateral denticles and a<br />

dominating, projecting, laterally compressed, noselike<br />

central keel; anthercap not seen; pollinarium of<br />

two globose cleft pollinia on a ca. 2 mm long and<br />

narrow stipe on a pulvinate viscidium.<br />

ParatyPe: Colombia, Magdalena, Sierra Nevada de<br />

Sta. Marta, Transecto del Alto Rio Buritaca, Cuchilla<br />

dalStröm — A new Cyrtochilum from Santa Marta, Colombia 145<br />

at 2700 m, Lev. 27. Proyecto Desarrollo, 2 August<br />

1977, R. Jaramillo M. et al. 5352 (COL).<br />

diStribution: Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Colombia.<br />

etymoloGy: Named in reference to the main color of<br />

the flower.<br />

Cyrtochilum violaceum is so far only reported<br />

from the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta region in<br />

northern Colombia. The poorly explored forests of<br />

this isolated mountain are likely to contain a large<br />

number of endemic species, both in the fauna and<br />

the flora. Several attractive orchid species have been<br />

described from there that are found nowhere else, such<br />

as Odontoglossum naevium Lindl., and O. nevadense.<br />

Rchb.f.<br />

aCknowledGment. I wish to thank Mariano Ospina for<br />

bringing the specimens to the US, and thus making them<br />

available to the author. I also wish to thank Wesley Higgins<br />

for reviewing and commenting on the manuscript.<br />

LANKESTERIANA <strong>12</strong>(3), December 20<strong>12</strong>. © Universidad de Costa Rica, 20<strong>12</strong>.

LANKESTERIANA

LANKESTERIANA <strong>12</strong>(3): 147—153. 20<strong>12</strong>.<br />

THREE NEW SMALL-FLOWERED CYRTOCHILUM SPECIES<br />

(ORCHIDACEAE: ONCIDIINAE) FROM COLOMBIA AND PERU,<br />

AND ONE NEW COMBINATION<br />

StiG dalStröm 1,3 & Saul ruíz Pérez 2<br />

1 2304 Ringling Boulevard, unit 119, Sarasota FL 34237, U.S.A.<br />

Lankester Botanical Garden, University of Costa Rica, Cartago, Costa Rica<br />

and National Biodiversity Centre, Serbithang, Bhutan<br />

2 Allamanda 142, Surco, Lima 33, Peru<br />

3 Corresponding author: stigdalstrom@juno.com<br />

abStraCt. Three new small-flowered Cyrtochilum species from Colombia and Peru are here described, illustrated<br />

and compared with similar species, and with one new taxonomic combination. The first species differs from all<br />

other Cyrtochilum species by the curved horn-like structures on the lip callus. The second species differs from<br />

its most similar relative by a larger flower with a different column structure. The third species is distinguished<br />

by the three horn-like knobs at the apex of the column.<br />

key wordS: Cyrtochilum, Orchidaceae, Oncidiinae, new combination, new species, Colombia, Peru, taxonomy<br />

The Andean orchid genus Cyrtochilum Kunth, is<br />

rapidly growing in number of species as previously<br />

unexplored areas are targeted for botanical inventories,<br />

sometimes into areas that have been, or still are,<br />

considered “dangerous” by governments for various<br />

reasons. In other cases, new species are found in<br />

herbaria where they have been laying undetermined in<br />

peaceful anonymity for years. This article presents two<br />

new species from the Cusco and Ayacucho regions in<br />

Peru, which has been terrorized by the Maoist guerilla<br />

known as “Sendero Luminoso” (Shining Path) for<br />

many years. Today smaller factions of this violent group<br />

apparently still control remote bases in the mountains<br />

between the city of Ayacucho and the Apurimac river to<br />

the east. What is left of the terrorist-like <strong>org</strong>anization is<br />

suspected to work as mercenaries for the illegal cocaine<br />

drug industry, also established in the region. In other<br />

words, this particular area is best given a wide berth!<br />

The third species described in this article is also from<br />

an area that until very recently was considered very<br />

dangerous to visit due to the activities of the FARC<br />

guerilla in Colombia. Great work has been done by the<br />

Colombian government, however, to clear most of the<br />

country from the dangers caused by this group.<br />

Cyrtochilum corniculatum Dalström, sp. nov.<br />

TYPE: Colombia. Antioquia, Yarumal, Km 87 along<br />

road Medellín-Yarumal, Llanos de Cuiba [Cuiva], 2750<br />

m, <strong>12</strong> Sep. 1984, C. Dodson et al. 15264 (holotype,<br />

RPSC; isotype, MO). fiG. 1.<br />

diaGnoSiS: Cyrtochilum corniculatum differs from<br />

all other small-flowered Cyrtochilum species by<br />

the combination of a column with two large ventral,<br />

lamellate angles, and a cordate, cupulate lip with a<br />

callus of two basal, falcate corniculate denticles.<br />

Epiphytic herb. Pseudobulbs apparently<br />

caespitose, subtended basally by 8 to 10 distichous<br />

sheaths, the uppermost foliaceous, ovoid, unifoliate or<br />

bifoliate, 8.0–9.0 × 2.5–3.0 cm. Leaves subpetiolate,<br />

conduplicate, obovate, acuminate, ca. 36.0–40.0 ×<br />

2.8–3.0 cm. Inflorescences multiple, axillary from<br />

the bases of the uppermost sheaths, wiry to ca. 1.5 m<br />

or longer panicles, with widely spaced, fractiflex or<br />

flexuous, 3 to 8-flowered side-branches. Floral bracts<br />

appressed, scale-like, 5.0–20.0 mm long. Pedicel<br />

with ovary 7.0–15.0 mm long. Flower stellate; dorsal<br />

sepal pinkish brown, shortly unguiculate to cuneate,<br />

elliptic to obovate laminate, obtuse to acute, 10.0–15.0<br />

× 6.0–7.0 mm; lateral sepals similar in color, shortly<br />

unguiculate to narrowly cuneate, obovate laminate,<br />

acute, <strong>12</strong>.0–13.0 × 5.0–6.0 mm; petals similar in color,<br />

unguiculate, slightly obliquely ovate laminate, obtuse<br />

to acute, 10.0–<strong>12</strong>.0 × 5.0 mm; lip similar in color,

148 LANKESTERIANA<br />

fiGure 1. Cyrtochilum corniculatum. A. Plant habit. B. Flower lateral view. C. Column, lateral and ventral views, and<br />

pollinarium. D. Flower dissected. Drawn from holotype by Stig Dalström.<br />

LANKESTERIANA <strong>12</strong>(3), December 20<strong>12</strong>. © Universidad de Costa Rica, 20<strong>12</strong>.

dalStröm and ruíz Pérez — Three new species of Cyrtochilum from Colombia and Peru 149<br />

rigidly fused to the base of the column and angled<br />

downwards in a ca. 135° angle, cordate to weakly<br />

trilobate, with spreading, rounded side lobes, and a<br />

cupulate involute, emarginate front lobe, ca. 10.0 × 5.0<br />

mm; callus yellow, of a low basal swelling with a pair<br />

of forward projecting, falcate corniculate denticles;<br />

column stout, erect, with a pair of ventral, forward<br />

projecting, laterally flattened and slightly incurved<br />

angles, and a truncate apex, ca. 5.0 mm long; anther<br />

cap not seen; pollinarium of two globose, cleft, or<br />

folded, pollinia on a minute ca. 0.7 mm long stipe, on<br />

a 0.5 mm long, pulvinate viscidium.<br />

ParatyPe: Colombia. Cundinamarca (?), “Bogota”,<br />

“Falkenberg” s.n.; the quoted information is marked<br />

with question marks on the herbarium sheet (W 15932).<br />

diStribution: Recorded from the Llanos de Cuiva area<br />

in the central cordillera of the Colombian Andes, at an<br />

elevation of 2750 m, and once (questionable) from the<br />

eastern cordillera, possibly somewhere near Bogota.<br />

etymoloGy: Named in reference to the falcate, hornlike<br />

denticles of the lip callus.<br />

Cyrtochilum corniculatum is only known from<br />

two collections, which is remarkable since it comes<br />

from rather heavily collected regions. The habitat is<br />

epiphytic in patches of upper elevation cloud forest,<br />

in rather deforested areas. The insignificant pinkish<br />

brown flowers on long and wiry inflorescences may<br />

have contributed to the plant not being observed or<br />

appreciated by previous collectors.<br />

Cyrtochilum russellianum Dalström & Ruíz-Pérez,<br />

sp. nov.<br />

TYPE: Peru. Ayacucho, La Mar, Aina, Calicanto,<br />

humid cloudforest at 2500-2600 m, collected by S.<br />

Ruíz, J. Valer and S. Dalström of Peruflora, 5 Dec.<br />

2010, S. Dalström 3415 (holotype, USM). fiG. 2.<br />

diaGnoSiS: Cyrtochilum russellianum is most similar<br />

to the sympatric Cyrtochilum carinatum (Königer<br />

& Deburghgr.) Dalström, comb. nov. (Basionym:<br />

Trigonochilum carinatum Königer & Deburghgr.,<br />

Arcula 19: 430. 2010), but differs primarily in having a<br />

larger flower without the well-developed dorsal column<br />

ridge, which ends in a distinct apical knob, typical for<br />

C. carinatum. It differs from the also sympatric C.<br />

sharoniae Dalström, by the light rose flowers versus<br />

dark blackish purple flowers of the latter species.<br />

Epiphytic herb. Pseudobulbs caespitose, ovoid,<br />

unifoliate or bifoliate, surrounded basally by<br />

distichous, foliaceous sheaths. Leaves subpetiolate,<br />

conduplicate (no vegetative parts exist in the type<br />

specimen. The relatively large type plant was examined<br />

but unfortunately not measured). Inflorescence axillary<br />

from the uppermost sheaths, erect, then more or less<br />

wiry, to ca. 1.8–2.0 m long panicle with widely spaced<br />

4- to 6-flowered flexuous side-branches. Floral bracts<br />

appressed, scale-like ca. 3.0–5.0 mm long. Pedicel with<br />

ovary triangular in cross-section and slightly winged,<br />

ca. 25 mm long. Flower stellate with more or less<br />

deflexed segments; dorsal sepal white almost covered<br />

by pale rose blotches, spathulate, elliptic laminate,<br />

acute, slightly undulate, <strong>12</strong>.0 × 5.0 mm; lateral sepals<br />

similar in color, spathulate, ovate laminate, obtuse,<br />

slightly oblique ca. <strong>12</strong>.0 × 4.0 mm; petals similar in<br />

color, shortly spathulate, obliquely obovate to rotund<br />

laminate, acuminate, 10.0 × 6.0 mm; lip whitish to<br />

pale yellowish with pale brown to purple spots, rigidly<br />

attached to the base of the column, hastate, triangular<br />

with distinctly angled side lobes and an obtuse slightly<br />

revolute, recurved and apically convolute front lobe,<br />

ca. 10.0 × 7.0 mm; callus pale yellowish with brown<br />

spots, of a fleshy, multidentate structure, extending<br />

from the base to about half the length of the lamina,<br />

with spreading, rounded knobs, and ending in a central,<br />

slightly larger rounded denticle, with two lateral,<br />

spreading, short, knoblike denticles; column lilac,<br />

erect, almost straight to slightly sigmoid, with a basal,<br />

ventral knoblike swelling, and then with two spreading<br />

ventral angles below the stigmatic surface, ca. 4.5–5.0<br />

mm long; anther cap red, globular; pollinarium of two<br />

elongate pyriform, cleft, or folded pollinia on a minute<br />

linear stipe, on a micro-minute pulvinate viscidium.<br />

diStribution: Cyrtochilum russellianum is only known<br />

from a single locality; the upper elevation cloudforests<br />

near the village of Calicanto, east of Ayacucho, Peru,<br />

in the centre of the former terrorist controlled area, at<br />

ca 2500 to 2600 m, where it is protected by some very<br />

suspicious and probably battle hardened villagers.<br />

ePonymy: Named in honor and gratitude of Russell F.<br />

Stephens Jr., of Sarasota, Florida, who has supported<br />

LANKESTERIANA <strong>12</strong>(3), December 20<strong>12</strong>. © Universidad de Costa Rica, 20<strong>12</strong>.

150 LANKESTERIANA<br />

fiGure 2. Cyrtochilum russellianum. A. Flower lateral and frontal views. B. Column lateral and ventral views. C. Anther cap<br />

and pollinarium. D. Flower dissected. Drawn from holotype by Stig Dalström.<br />

LANKESTERIANA <strong>12</strong>(3), December 20<strong>12</strong>. © Universidad de Costa Rica, 20<strong>12</strong>.

dalStröm and ruíz Pérez — Three new species of Cyrtochilum from Colombia and Peru 151<br />

orchid research by establishing the Friends of Orchid<br />

Research Fund (with a particular interest in the orchid<br />

flora of Bhutan and Peru), administrated by the<br />

Community Foundation of Sarasota County.<br />

Cyrtochilum russellianum is similar to and<br />

flowers simultaneously with the sympatric and pale<br />

pink-flowered C. carinatum, but differs in the larger<br />

flower without a distinct dorsal keel and apical knob<br />

on the column. The similarly small flowered C.<br />

sharoniae also grows sympatrically in the same area<br />

and flowers simultaneously with C. carinatum and C.<br />

russellianum, but differs in the dark purple to almost<br />

blackish flowers. All three species have lilac columns,<br />

a very unusual and interesting circumstance. The<br />

vegetative differences, however, are clear between the<br />

three species. The pseudobulbs in C. russellianum are<br />

normally green, while in C. carinatum the base of the<br />

pseudobulbs as well as the base of the new growths<br />

are dark purplish in the wild. The pseudobulbs in C.<br />

sharoniae are typically dark green and the leaves have<br />

a whitish wax-like coating, similar to some unrelated<br />

plants with a pendent habit, such as Euchile citrina<br />

(Lex.) Withner, and Masdevallia caesia Roezl.<br />

Cyrtochilum tricornis Dalström & Ruíz-Pérez, sp.<br />

nov.<br />

TYPE: Peru. Cusco, Quillabamba, Rio Chullapi<br />

Reserva, 2000—2200 m, field collected by Luis<br />

Valenzuela and his team from the Cusco University,<br />

with J. Sönnemark and S. Dalström, 9 Dec. 2002, S.<br />

Dalström et al. 2699 (holotype, CUZ). fiG. 3.<br />

diaGnoSiS: Cyrtochilum tricornis is most similar to<br />

C. cimiciferum (Rchb.f.) Dalström, and Cyrtochilum<br />

macropus (Linden & Rchb.f.) Kraenzl., but differs<br />

from both by the much smaller floral bracts, the<br />

pandurate lip lamina and the three distinct horn-like<br />

structures at the apex of the column.<br />

Epiphytic herb. Pseudobulbs caespitose, ovoid,<br />

bifoliate, 9.0–11.0 × 1.5–2.0 cm, surrounded basally<br />

by 6 to 8 distichous sheaths, the uppermost foliaceous.<br />

Leaves subpetiolate, conduplicate, elliptic to obovate,<br />

narrowly acute to acuminate, 29.0–35.0 × 1.0–2.0<br />

cm. Inflorescence 1 or 2, axillary from the uppermost<br />

sheaths, erect to arching, almost straight to slightly<br />

flexuous apically, to ca. 130 cm long panicle, with many<br />

widely spaced, almost straight to slightly flexuous, 3-<br />

to 6-flowered side-branches. Floral bracts appressed,<br />

scale-like, ventrally pubescent, acute, 5.0–10.0 mm<br />

long. Pedicel with ovary 20.0–25.0 mm long. Flowers<br />

stellate with deflexed segments; dorsal sepal yellow<br />

with brown spots, unguiculate to spathulate, obovate to<br />

elliptic laminate, obtuse, weakly undulate, and slightly<br />

revolute, ca. 10.0 × 4.0–5.0 mm; lateral sepals similar<br />

in color, spathulate, narrowly and obliquely ovate to<br />

elliptic laminate, obtuse, 15.0 × 6.0 mm; petals similar<br />

in color, broadly unguiculate, broadly and slightly<br />

obliquely ovate, almost rotundate laminate, obtuse, ca.<br />

10.0 × 6.0 mm; lip similar in color, rigidly attached to<br />

the base of the column, basally hastate, trilobate and<br />

pandurate with distinct lateral angles, and a rounded,<br />

concave, strongly reflexed front lobe, ca. 10.0 × 6.0–<br />

7.0 mm; callus yellow, of a fleshy, tricarinate structure,<br />

emerging from the base of the lip and longitudinally<br />

extending for about 4.0–5.0 mm, the lateral ridges<br />

being shorter and ending in blunt, slightly spreading<br />

angles, and the central ridge ending in a slightly<br />

swollen, rounded knob; column basally green, then<br />

purplish or brownish, apically yellow, erect in a ca. 90º<br />

angle from the base of the lip, stout, straight, with two<br />

diffuse spreading, lateral angles, and one central fleshy<br />

keel below the stigmatic surface, and three apical<br />

horn-like structures, 4–5 mm long; anther cap dark<br />

orange to red, with a yellow dorsal stripe, campanulate<br />

and minutely papillose; pollinarium of two elongate<br />

pyriform, cleft, or folded, pollinia on a minute, less<br />

than 0.5 mm long broadly linear, or rectangular, stipe<br />

on a minute, almost triangulate, pulvinate viscidium.<br />

ParatyPeS: Peru. Pasco, Paucartambo, Ulcumayo,<br />

Anexo Yaupi, ca. 2000—2200 m, humid forest at ca<br />

1800—2000 m, field collected by S. Ruíz s.n., and<br />

flowered in cultivation at Perúflora, 26 Dec. 2011,<br />

S. Dalström 3493 (USM). Same area, 5 km south<br />

of Oxapampa, ca. 1800 m, 30-31 Jan. 1979, C. &<br />

J. Luer 3817, 3837 (SEL). Same area. Oxapampa,<br />

Chontabamba, <strong>12</strong>00 m, 17 July 1996, J. del Castillo<br />

s.n., ex D. E. Bennett 7672; illustration in Icones<br />

Orchidacearum Peruviarum, pl. 533 (1998), as<br />

“Oncidium saltabundum” (<strong>No</strong> preserved specimen<br />

found).<br />

diStribution: This species is only known from<br />

montane areas in the departments of Pasco and Cusco<br />

LANKESTERIANA <strong>12</strong>(3), December 20<strong>12</strong>. © Universidad de Costa Rica, 20<strong>12</strong>.

152 LANKESTERIANA<br />

fiGure 3. Cyrtochilum tricornis. A. Plant habit. B. Flower lateral view. C. Column lateral and ventral views, and anther cap.<br />

D. Pollinarium, with front and lateral views of the stipe. E. Flower dissected. Drawn from holotype by Stig Dalström.<br />

LANKESTERIANA <strong>12</strong>(3), December 20<strong>12</strong>. © Universidad de Costa Rica, 20<strong>12</strong>.

dalStröm and ruíz Pérez — Three new species of Cyrtochilum from Colombia and Peru 153<br />

in central Peru where it occurs as an epiphyte in open<br />

and humid forests at <strong>12</strong>00-2200 m elevation.<br />

etymoloGy: The name refers to the three horn-like<br />

structures at the apex of the column.<br />

Cyrtochilum macropus has in previous treatments<br />

been considered as a synonym of C. cimiciferum<br />

(Dalström, 2001), but recent examinations of additional<br />

field-collected material and the holotypes show that it<br />

should be treated as a distinct species.<br />

literature Cited<br />

aCknowledGment. The authors wish to thank the staff<br />

at the Instituto Recursos Naturales (INRENA), and<br />

Betty Millán at the Universidad de San Marcos, Museo<br />

de Historia Natural, Lima, for aiding in providing the<br />

necessary collecting permits. We also wish to thank the staff<br />

at the herbaria of CUZ, MO, MOL, SEL and USM, for their<br />

assistance in the examinations of preserved plant specimens.<br />

We also thank Wesley Higgins for viewing and commenting<br />

on the manuscript, Jan Sönnemark of Halmstad, Sweden,<br />

for great field company and support, and the Perúflora staff<br />

together with the Manuel Arias family in Lima for generous<br />

logistic support.<br />

Dalström, S. – 2001. A synopsis of the genus Cyrtochilum (Orchidaceae; Oncidiinae): Taxonomic reevaluation and new<br />

combinations. Lindleyana 16(2): 56-80.<br />

LANKESTERIANA <strong>12</strong>(3), December 20<strong>12</strong>. © Universidad de Costa Rica, 20<strong>12</strong>.

LANKESTERIANA

LANKESTERIANA <strong>12</strong>(3): 155—160. 20<strong>12</strong>.<br />

A WELL-KNOWN BUT PREVIOUSLY MISIDENTIFIED ODONTOGLOSSUM<br />

(ORCHIDACEAE: ONCIDIINAE) FROM ECUADOR<br />

StiG dalStröm<br />

2304 Ringling Boulevard, unit 119, Sarasota FL 34237, U.S.A.<br />

Lankester Botanical Garden, University of Costa Rica, Cartago, Costa Rica<br />

and National Biodiversity Centre, Serbithang, Bhutan<br />

stigdalstrom@juno.com<br />

abStraCt. A previously misidentified species of Odontoglossum (Orchidaceae, Oncidiinae), from the botanically<br />

well explored western slopes of mount Pichincha in Ecuador is described and illustrated, and compared with<br />

similar species. The new species is most similar to O. cristatum, but differs in a larger plant habit with larger<br />

flowers that present a longer and straighter column with bifurcate wings, versus a more slender and more curved<br />

column with triangular, falcate column wings of O. cristatum.<br />

key wordS: Orchidaceae, Oncidiinae, Odontoglossum, new species, Pichincha, Ecuador, taxonomy<br />

The genus Odontoglossum Kunth, (treated by<br />

some authors as Oncidium) consists of some of the<br />

most stunningly beautiful orchids that exist, and that<br />

have appealed to, and mesmerized not only orchid<br />

people around the world for almost two centuries.<br />

Odontoglossum species are also some of the most<br />

difficult to define taxonomically due to a variety<br />

of reasons. Their’ impressive natural variation and<br />

floral plasticity may be the very reason why they are<br />

so attractive to growers but also turn taxonomy into<br />

a serious befuddlement. The species described here<br />

has been known to orchid collectors and growers<br />

for a long time but hiding under a different name,<br />

“Odontoglossum cristatum” (e.g. Bockemühl 1989:<br />

56–58). Although our new species resembles the true<br />

O. cristatum Lindl., and a couple of other similar<br />

species in several aspects, it can be distinguished by a<br />

unique combination of features. Each feature may be<br />

shared by one or several other species but not in the<br />

same combination.<br />

Odontoglossum furcatum Dalström, sp. nov.<br />

TYPE: Ecuador. Pichincha: Near Tandapi, at 1800 m,<br />

Oct. 1982. A. Hirtz 368 (holotype, SEL). fiG. 1,, 2, 3C,<br />

2C1.<br />

diaGnoSiS: Odontoglossum furcatum is most similar to<br />

O. cristatum Lindl. (Fig. 3A, 3A1, 4), which occurs<br />

further to the south in Ecuador, near the towns of<br />

Zaruma and Paccha at a similarly low elevation (<strong>12</strong>00–<br />

1500 m), but differs in a larger plant habit with larger<br />

flowers that present a longer and straighter column with<br />

the typical bifurcated wings, versus a more slender and<br />

more curved column with triangular, shark-fin shaped,<br />

falcate column wings of O. cristatum. Odontoglossum<br />

hallii Lindl. (Fig 3D, 3D1, 5), has similar bifurcate<br />

column wings but occurs at much higher elevations,<br />

generally around 2800–3200 m, and exhibits larger<br />

flowers with a much broader, often pandurate, deeply<br />

lacerate lip. Odontoglossum cristatellum Rchb.f. (Fig.<br />

3B, 3B1, 6), also exists at a higher elevation, generally<br />

between 2500–3000 m, and has a shorter and stouter<br />

column with broad, usually rectangular wings.<br />

Epiphytic herb. Pseudobulbs caespitose, ancipitous,<br />

slightly compressed, glossy, ovoid, bifoliate, ca. 7.0 ×<br />

2.5–3.0 cm, surrounded basally by 7 to 9 distichous<br />

sheaths, the uppermost foliaceous. Leaves subpetiolate,<br />

conduplicate, narrowly obovate to elliptic, acuminate,<br />

20.0–28.0 × 1.8–2.0 cm. Inflorescences axillary from<br />

the base of the uppermost sheaths, suberect and<br />

arching to subpendent, to ca. 45 cm long, weakly<br />

flexuous to almost straight, to ca. 10 flowered racemes.<br />

Floral bracts appressed and scale-like, 5–15 mm long.<br />

Pedicel and ovary 20–30 mm long. Flowers relatively<br />

large, stellate to slightly campanulate, showy and<br />

scented but not overly pleasantly; dorsal sepal pale<br />

yellow with brown spots and markings, ovate to<br />

elliptic, slightly obliquely acuminate, entire, 40–45 ×<br />

<strong>12</strong>–14 mm; lateral sepals similar in color, unguiculate,

156 LANKESTERIANA<br />

fiGure 1. Odontoglossum furcatum. A. Plant habit. B. Column and lip lateral view. C. Lip front view. D. Column lateral<br />

view. E. Column ventral view. F. Anthercap and pollinia dorsal, lateral and back view. G. Flower dissected. Drawn from<br />

holotype by Stig Dalström.<br />

LANKESTERIANA <strong>12</strong>(3), December 20<strong>12</strong>. © Universidad de Costa Rica, 20<strong>12</strong>.

fiGure 2. Odontoglossum furcatum, inflorescence from the<br />

plant that served as the holotype. Photo by S. Dalström.<br />

obliquely ovate, acuminate, entire, ca. 40 × <strong>12</strong> mm;<br />

petals similar in color, unguiculate, obliquely ovate,<br />

acuminate, entire, ca. 40 ×14 mm; lip similar in color,<br />

attached to the basal and lateral flanks of the column for<br />

ca. 4 mm, then free via a flat and narrow strap-like, ca.<br />

2 mm long claw, then widening into short erect lateral<br />

lobes, then distinctly angled downwards into a large,<br />

cordate to broadly ovate, slightly crenulate or serrate,<br />

obtuse, apically convolute and acuminate lip lamina,<br />

ca. 35 × 16–17 mm; callus white to pale yellow with<br />

red-brown longitudinal stripes and spots, consisting<br />

of evenly spreading laterally flattened, fleshy keels,<br />

becoming larger towards the center and with additional<br />

uneven dorsal angles and fleshy tendrils; column white<br />

with some brown markings apically, erect, elongate,<br />

slightly curved downwards towards the apex, with<br />

lateral keels emerging basally and extending to, and<br />

angled just beneath the stigma, and with generally<br />

distinct and slightly variable bifurcate apical wings,<br />

ca. 20 mm long; anthercap campanulate rostrate with a<br />

dalStröm — A new Odontoglossum from Pichincha, Ecuador 157<br />

dorsal lobule; pollinarium of two cleft/folded pyriform<br />

pollinia on an elongate rectangular, apically obtuse ca.<br />

3.5–4.0 mm long stipe, on a conspicuously hooked<br />

pulvinate viscidium.<br />

ParatyPeS: Ecuador. Carchi: Maldonado, 1800 m, without<br />

date, A. Andreetta 0230 (SEL). Pichincha: Andes of Quito,<br />

ca. 2300 m, August without date, W. Jameson 35 (K). Mt.<br />

Pichincha, 4100-4500 m[?; improbable altitude-probably<br />

feet], 17 Aug. 1923, A. S. Hitchkock 21934 (US). Above<br />

Tandapi, 1550 m, 14 Mar. 1982, S. Dalström 161 (SEL).<br />

Km 80 along road Quito–Santo Domingo, 1500 m, 27 Sept.<br />

1980, C. H. Dodson et al. 10557 (MO, RPSC, SEL). Same<br />

area, 1800 m, 20 June 1985, C. H. & T. Dodson 15855<br />

(MO). Tandayapa, road <strong>No</strong>no–Nanegal, 2000 m, collected<br />

and flowered in cultivation by A. Andreetta, 25 Feb. 1982,<br />

C. H. Dodson <strong>12</strong>859 (SEL). Ca 6 km SE of Nanegal, 2000<br />

m, 6 Sept. 1993, G. L. Webster et al. 30382 (UC-Davis).<br />

Mindo, collected Dec. 1992 and flowered in cultivation<br />

by J. Sönnemark in 1993 without date, S. Dalström 2065<br />

(SEL). Imbabura: Above Garcia Moreno, 1800 m, collected<br />

and flowered in cultivation by J. Sönnemark, Dec. 1992,<br />

S. Dalström et al. 2070 (SEL). Cotopaxi: Pujilí, Reserva<br />

Ecológica Los Illinizas, sector 11, sector Chuspitambo,<br />

W of Choasilli, 0°58’42” S, 79°06’22”W, 1760 m, 3 Aug.<br />

2003, P. Silverstone-Sopkin et al. 9736 (CUVC, SEL). La<br />

Maná, Reserva Ecológica Los Illinizas, sector El Oriente,<br />

access from Carmela, 0°40’18”S, 78°04’45”W, 1572 m,<br />

14 July 2003, P. Silverstone-Sopkin et al. 9155 (CUVC,<br />

SEL).<br />

diStribution: <strong>No</strong>rthwestern slopes of the Andes in<br />

Ecuador, at 1500–2300 m.<br />

etymoloGy: The name refers to the furcated (forked)<br />

column wings.<br />

The earliest examined documentation of<br />

Odontoglossum furcatum is a nineteenth century<br />

collection by William Jameson from the “Andes of<br />

Quito”, deposited at Kew. It shows a compact plant with<br />

a short inflorescence carrying two flowers and one bud,<br />

mounted between two specimens of O. hallii. This O.<br />

furcatum specimen was determined as “Odontoglossum<br />

cristatum” by Bockemühl in 1985. Indeed, these two<br />

species are closely related and resemble each other in<br />

several ways. The type of O. cristatum was collected by<br />

Theodore Hartweg in southern Ecuador near the town<br />

of Paccha, perhaps contemporary with the Jameson<br />

collection, and it has been observed in recent years by<br />

Dalström, growing at <strong>12</strong>00–1500 m, an uncommonly<br />

LANKESTERIANA <strong>12</strong>(3), December 20<strong>12</strong>. © Universidad de Costa Rica, 20<strong>12</strong>.

158 LANKESTERIANA<br />

fiGure 3. A. Odontoglossum cristatum (C. Dodson 13168, SEL), flower dissected; A1. Column lateral and ventral views.<br />

B. Odontoglossum cristatellum (S. Dalström 556, SEL) , flower dissected; B1. Column lateral and ventral views. C.<br />

Odontoglossum furcatum (A. Hirtz 368, SEL), flower dissected; C1. Column lateral and ventral views. D. Odontoglossum<br />

hallii (S. Dalström 650, SEL), flower dissected; D1. Column lateral and ventral views. Drawn by Stig Dalström.<br />

low altitude for the genus. The flowers of O. cristatum<br />

are smaller in general and the column more slender<br />

and with differently shaped wings than O. furcatum.<br />

Although some natural variation occur in both species<br />

and occasional plants have been found that resemble<br />

intermediate forms, plants displaying the typical<br />

morphology of O. cristatum are not sympatric with O.<br />

furcatum. The bifurcate column wings of O. furcatum<br />

LANKESTERIANA <strong>12</strong>(3), December 20<strong>12</strong>. © Universidad de Costa Rica, 20<strong>12</strong>.<br />

strongly resemble the wings of O. halli, which is a<br />

higher elevation species that displays larger flowers<br />

with a very different looking lip that easily separates<br />

the two taxa. Odontoglossum cristatellum may<br />

superficially resemble O. furcatum but is distinguished<br />

by the stout column with broad, generally rectangle<br />

column wings. Occasionally O. cristatellum can have<br />

more triangular column wings, resembling those of O.

fiGure 4. Odontoglossum cristatum. Ecuador. El Oro, S.<br />

Dalstrúom 962. Photograph by S. Dalström.<br />

dalStröm — A new Odontoglossum from Pichincha, Ecuador 159<br />

fiGure 5. Odontoglossum hallii. Ecuador. Imbabura, S.<br />

Dalstrúom 738. Photograph by S. Dalström.<br />

fiGure 6. Odontoglossum cristatellum. Ecuador. Loja, S. Dalström 2772. Photograph by S. Dalström.<br />

LANKESTERIANA <strong>12</strong>(3), December 20<strong>12</strong>. © Universidad de Costa Rica, 20<strong>12</strong>.

160 LANKESTERIANA<br />

cristatum and occasionally some intermediate forms<br />

are seen, possibly resulting from natural hybridization<br />

in areas where the two species occur in reasonably<br />

close proximity, a phenomenon often reported in<br />

Odontoglossum.<br />

LANKESTERIANA <strong>12</strong>(3), December 20<strong>12</strong>. © Universidad de Costa Rica, 20<strong>12</strong>.<br />

aCknowledGment I wish to thank Wesley Higgins for<br />

viewing and commenting on the manuscript.<br />

literature Cited<br />

Bockemühl, L. 1989. Odontoglossum, a monograph<br />

and iconograph. Brücke-Verlag Kurt Schmersow,<br />

Hildesheim, Germany.

LANKESTERIANA <strong>12</strong>(3): 161—164. 20<strong>12</strong>.<br />

PONTHIEVA HERMILIAE, A NEW SPECIES OF ORCHIDACEAE IN THE<br />

CORDILLERA YANACHAGA (OXAPAMPA, PASCO, PERU)<br />

luiS valenzuela Gamarra<br />

Missouri Botanical Garden. Prolongación Bolognesi Mz. E Lote 6, Oxapampa-Pasco, Perú<br />

luis_gin@yahoo.es<br />

abStraCt. A new species of Ponthieva was found in the mountains of Yanachaga Chemillén, on a pre-montane<br />

forest at 1400 m in the central jungle of Peru. It is similar to P. pilosissima, but can be distinguished by the<br />

presence of a callus on the lip and by the color of the petals, which are boldly veined in P. pilosissima and<br />

inconspicuously striped in P. hermiliae.<br />

key wordS: Orchidaceae, Orchidoideae, Ponthieva, new species, Peru, Yanachaga<br />

The Orchidaceae family amazes most researchers<br />

because of its great diversity, with more than 28,000<br />

species worldwide (Govaerts et al. 20<strong>12</strong>). Just below<br />

2,900 have been reported to grow in Peru (Zelenko &<br />

Bermudez 2009), however, considering the vastness<br />

of the territory and diversity in complex ecosystems,<br />

those numbers will probably increase. The Cordillera<br />

Yanachaga Chemillén, located in the Oxapampa<br />

province, is a region that has remained unexplored<br />

and is likely to host orchid species not yet known to<br />

science.<br />

Globally there are a little over 3600 species of<br />

Orchidoideae (Bateman et al. 2003), which mainly<br />

share terrestrial habits. Members of the subfamily are<br />

characterized by a single fertile upright anther with<br />

sectile pollinia. The genus Ponthieva was named in<br />

honor of Henri Ponthieu, a French merchant who was<br />

sending plant collections from the West Indies to Mr.<br />

Joseph Banks in 1778. The genus is distributed from<br />

the southern United States, Mexico, Caribbean to<br />

southern Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Bolivia.<br />

They are mainly terrestrial plants but occasionally<br />

grow epiphytically. They have thickened fibrous roots,<br />

covered by long soft hairs and a stem that develops<br />

from the rhizomes. The flowers are arranged on a<br />

cluster inflorescences, with bracteate peduncles. The<br />

dorsal sepal is apically fused to the petals, which may<br />

or may not be fused to the sides of the column (Dodson<br />

& Escobar 2003).<br />

Ponthieva hermiliae L.Valenzuela, sp. nov.<br />

Type: Peru. Pasco, Oxapampa, Yanachaga Chemillén<br />

National Park, 1400 m. 10°24’36”S 075°19’48”W. L.<br />

Valenzuela 20064, M. I. Villalba, J. Mateo & R. Rivera<br />

(holotype, HOXA). Fig. 1, 2a–C.<br />

Species Ponthievae pilossimae (Sengh.) Dodson<br />

similis, petalibus distincte callosis in parte basali<br />

dilute brunneo striato-maculatis, labello basaliter<br />

exauriculato, calli margo proximalis rotundato non<br />

exciso praecipue recedit.<br />

Epiphytic herb, up to 46 cm tall including the<br />

inflorescence. Leaves spathulate-elliptic, flexuous, 24–<br />

26 × 2.0–2.5 cm, covered by clavate, glandular hairs 1<br />

mm long. Inflorescence a successively many-flowered<br />

raceme with 5-7 flowers opened at once. Floral bracts<br />

1.5 cm long, hairy. Pedicellate ovary covered with<br />

trichomes, 3 cm long including the pedicel. Sepals<br />

lanceolate, the lateral falcate-lanceolate, covered<br />

externally with glandular trichomes, yellowish green<br />

marked with brown at the insertion point, 1.0-2.0 × 0.4–<br />

0.5 cm. Petals oblong-lanceolate, 1.9–2.0 × 0.25–0.30<br />

cm, whitish green with a faint, parallel, light brown<br />

venation, provided with an ellipsoid callus located in the<br />

lower quarter. Lip yellowish-green to greenish-white, 6<br />

mm long, lanceolate-triangular, slightly concave in the<br />

proximal half and at the rear, with a 6-toothed callus<br />

arranged horizontally in front of the basal cavity. Anther<br />

cap ovate-triangular, cucullate, verrucose, dark green.<br />

Pollinia 4 in two pairs, clavate, 1 mm long, supported<br />

by a flexible elongate stipe.<br />

diStribution and eColoGy: Epiphyte found on the<br />

eastern flank of the Cordillera Yanachaga Chemillén,<br />

where it is apparently restricted to constantly foggy,

162 LANKESTERIANA<br />

fiGure 1. Ponthieva hermiliae L.Valenzuela. A. Habit. B.Flower and detail of the inflorescence. C. Sepals. D. Petals. E.<br />

Column and lip, frontal view. F. Column and lip, lateral view. G. Anther cap, ventral view. H. Anther cap, dorsal view. I.<br />

pollinarium. J. Floral bract and pedicel. K. Hair. Drawn by the author from the holotype.<br />

LANKESTERIANA <strong>12</strong>(3), December 20<strong>12</strong>. © Universidad de Costa Rica, 20<strong>12</strong>.

premontane forest (fig. 2d). The plants are growing<br />

mainly on the root stem of tree ferns (Cyathea spp).<br />

ePonymy: The name honors Gina Hermila Gamarra<br />

Muñiz, the author’s mother.<br />

Ponthieva hermiliae is similar to P. pilosissima<br />

(Senghas) Dodson, but differs in exauriculate base of<br />

the lip (vs. with distinct retrorese lobes), the shape of<br />

the callus on the lip (rounded vs. excise), and the petals<br />

distinctly callose at the base, faintly striped with<br />

light brown (vs. obscurely callose, boldly striped with<br />

redish brown). Furthermore, the sepals of P. hermiliae<br />

are subsimilaar in size, whereas in P. pilosissima the<br />

dorsal sepal is much smaller (Senghas 1989).<br />

aCknowledGementS. The author wishes to thank Missouri<br />

Botanical Garden for the economic contribution and<br />

allowing scientific research in Peru, where many new taxa<br />

valenzuela - Ponthieva hermiliae 163<br />

fiGure 2. Ponthieva hermiliae. A. Flower. B–C. Details of the inflorescence. D. Habitat. Photographs by the author.<br />

are discovered and described to science. To Stig Dalström<br />

for help with the translation; to Rodolfo Vásquez M., Rocío<br />

del Pilar Rojas G. and María Isabel Villalba V. for their<br />

additions to the manuscript.<br />

literature Cited<br />

Bateman, R. M., P. M. Hollingsworth, J. Preston, L. Yi-<br />

Bo, A. M. Pridgeon & M. W. Chase. 2003. Molecular<br />

phylogenetics and evolution of Orchidinae and selected<br />

Habenariinae (Orchidaceae). Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 142:<br />

1–40.<br />

Dodson C. H. 1996. Nuevas Especies y Combinaciones de<br />

orquídeas ecuatorianas – 4 / New orchid species and<br />

Combination from Ecuador – 4. Orquideología 20 (1):<br />

90–111.<br />

Dodson, C. H. & R. Escobar. 2003. Orquídeas Nativas del<br />

Ecuador. Volumen IV. Oncidium-Restrepiopsis. Editorial<br />

Colina, Medellín.<br />

Govaerts, R., J. Pfahl, M.A. Campacci, D. Holland Baptista,<br />

LANKESTERIANA <strong>12</strong>(3), December 20<strong>12</strong>. © Universidad de Costa Rica, 20<strong>12</strong>.

164 LANKESTERIANA<br />

H. Tigges, J. Shaw, P. Cribb, A. Ge<strong>org</strong>e, K. Kreuz & J.<br />

Wood. 20<strong>12</strong>. World Checklist of Orchidaceae. The<br />

Board of Trustees of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.<br />

Senghas, K. 1989. Die Gattung Chranichis, mit einer neuen<br />

Art, Chranichis pilosissima, aus Ekuador. Orchidee<br />

LANKESTERIANA <strong>12</strong>(3), December 20<strong>12</strong>. © Universidad de Costa Rica, 20<strong>12</strong>.<br />

(Hamburg) 40 (2): 44-51.<br />

The Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (APG III). 2009.<br />

Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society (161): 105-<strong>12</strong>1.<br />

Zelenko H. & P. Bermúdez. 1999). Orchids: species of<br />

Peru. ZAI Publications. Quito, Ecuador.

LANKESTERIANA <strong>12</strong>(3): 165—173. 20<strong>12</strong>.<br />

SPECIES DIFFERENTIATION OF SLIPPER ORCHIDS<br />

USING COLOR IMAGE ANALYSIS<br />

erneSto Sanz 1 , noreen von Cramon-taubadel 2 & david l. robertS 3,4<br />

1 Departamento de Biología, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, C/Darwin, 2,<br />

E-28049 Madrid, Spain<br />

2 Department of Anthropology, School of Anthropology and Conservation, University of Kent,<br />

Marlowe Building, Canterbury, Kent CT2 7NR, U.K.<br />

3 Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology, School of Anthropology and Conservation,<br />

University of Kent, Marlowe Building, Canterbury, Kent CT2 7NR, U.K.<br />

4 Corresponding author: d.l.roberts@kent.ac.uk<br />

abStraCt. A number of automated species recognition systems have been developed recently to aid nonprofessionals<br />

in the identification of taxa. These systems have primarily used geometric morphometric based<br />

techniques, however issues surround their wider applicability due to the need for homologous landmarks.<br />

Here we investigate the use of color to discriminate species using the two horticulturally important slipper<br />

orchid genera of Paphiopedilum and Phragmipedium as model systems. The ability to differentiate the various<br />

taxonomic groups varied, depending on the size of the group, diversity of colors within the group, and the<br />

background of the image. In this study the image analysis was conducted with images of single flowers of the<br />

species, however since flowers are ephemeral, flowering for a relatively short period of time, such analysis<br />

should be extended to vegetative parts, particularly as this is the form in which they are most often traded<br />

internationally.<br />

reSumen. Una gran cantidad de sistemas de reconocimiento automático de especies se han desarrollado en los<br />

últimos años, como ayuda a aquellas personas que no son especialistas en la identificación de especies. Estos<br />

sistemas han utilizado sistemas de reconocimiento automático basados en geometría morfométrica, sin embargo<br />

existen límites debido a la necesidad de encontrar puntos de georreferenciación en los diferentes <strong>org</strong>anismos.<br />

En este artículo investigamos el uso de los colores para diferenciar especies en los géneros Paphiopedilum y<br />

Phragmipedium, ambos con gran importancia en la horticultura. La capacidad de discriminación varía entre los<br />

grupos taxonómicos, dependiendo del tamaño del taxón, la variedad de colores entre las especies y el fondo de<br />

las imágenes. En este estudio el análisis de imágenes se ha llevado a cabo con fotografías de flores individuales.<br />

<strong>No</strong> obstante dado que las flores son órganos efímeros, en el futuro esta investigación incluirá partes vegetativas,<br />

ya que es en estado vegetativo la forma en la que se suele comerciar internacionalmente más a menudo.<br />

key wordS: digital, discrimination, Orchidaceae, Paphiopedilum, photograph, Phragmipedium<br />

Introduction. The scientific community is facing<br />

a taxonomic crisis. Linnean shortfall, a euphemism<br />

for the hole in our knowledge of biodiversity, cannot<br />

be estimated to within an order of magnitude (May<br />

1988). Faced with the vast number of species yet to<br />

be discovered, coupled with the diminishing training<br />

of new taxonomists (Hopkins & Freckleton 2002) and<br />

accelerating extinction rates (Pimm et al. 2006), the task<br />

of cataloguing Earth’s biodiversity is immense. Accurate<br />

species identification is key to meeting this challenge,<br />

however misidentification is an ever-present problem.<br />

For some species, routine assessments, such as counting<br />

the dorsal spines of stickleback fish (Gasterosteidae),<br />

can result in accuracies as high as 95%. For others more<br />

experience is required, and in some cases inconsistent<br />

identification can be over 40% (MacLeod et al. 2010).<br />

To reduce such errors we rely on expert opinion for<br />

the verification of a taxon’s identity. Border agencies<br />

are interested in identifying species controlled under<br />

CITES, agriculturalists in pest species, building<br />

developers in legally protected species, the horticultural<br />

industry in difference between new hybrids, as well as

166 LANKESTERIANA<br />

the amateur naturalist communities’ general interest.<br />

Rapid and precise identifications are important for<br />

society as a whole. Computer-based automated species<br />

recognition has therefore been suggested as a potential<br />

technology to aid in the rapid identification of species,<br />

particularly taxa that form part of routine investigations<br />

(MacLeod et al. 2010).<br />

Automated species recognition largely focused on<br />

using geometric morphometic-based techniques, such<br />

as the elliptic Fourier description and landmark analysis<br />

(MacLeod et al. 2010). The problem is that, at least for<br />

landmark analysis, they rely on homologous points.<br />

For example in face recognition (Shi et al. 2006), the<br />

tip of a nose may be considered homologous (in the<br />

sense of evolutionary origins, growth and development<br />

etc.) as that of another human, however the further we<br />

move away from the same species or taxon the more<br />

difficult it becomes to place the landmark (e.g. where<br />

would you place the same landmark on an insect or<br />

an orchid?). The issue surrounding homology of<br />

landmarks reduces their applicability, resulting in the<br />

proliferation of individual bespoke systems. Color<br />

has, however, only been used rarely within the field<br />

of species recognition (Das et al. 1999; Nilsback &<br />

Zisserman 2008). Here we investigate whether orchids<br />

can be differentiated based on color. Specifically we<br />

look the slipper orchid genera, Paphiopedilum and<br />

Phragmipedium, due to their importance within the<br />

orchid horticultural industry and the fact that, being on<br />

Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade<br />

in Endangered Species, they are of particular concern<br />

to inspectors at border posts.<br />

Material and methods. A checklist of the two slipper<br />

orchid genera, Paphiopedilum and Phragmipedium,<br />

was constructed using the online World Checklist of<br />

Selected Flowering Plant Families (http://apps.kew.<br />

<strong>org</strong>/wcsp), and following the sectional delimitations<br />

of Cribb (1998; pers. comm.) and Pridegon et al.<br />

(1999). Digital images were then identified on the<br />

internet using a search engine (http://www.google.<br />

com/). Specifically we looked for images of species<br />

from the two genera that had approximately a black<br />

background, showed a single flower facing forward<br />

and minimal other parts of the plant. These images<br />

were then downloaded and a database was collated<br />

in Microsoft Excel. The downloaded images were<br />

LANKESTERIANA <strong>12</strong>(3), December 20<strong>12</strong>. © Universidad de Costa Rica, 20<strong>12</strong>.<br />

analyzed using the online Image Color Summarizer<br />

v0.5 (http://mkweb.bcgsc.ca/color_summarizer/). For<br />

each image, a text file was generated containing the<br />

pixel frequencies for red (R), blue (B), green (G), hue<br />

(H), saturation (S) and value (V). The setting ‘extreme’<br />

precision control was used.<br />

Factor analysis was performed to decompose the<br />

resultant variables obtained from the image analysis<br />

into principal components. Components which<br />

explained at least 1% of the total variance were<br />

extracted and used as input variables for a multivariate<br />

Discriminant Function Analysis (DFA). DFA was<br />

used in order to assess the extent to which the pixel<br />

frequency data could be employed to correctly<br />

classify individual specimens back to correct group.<br />

The analysis was conducted for all species, grouping<br />

by subgenus (in the case of Paphiopedilum) and by<br />

taxonomic section (in the case of Phragmipedium and<br />

each subgenus of Paphiopedilum). From these analyses<br />

we focused on the leave-one-out classification, (a) the<br />

percentage original grouped cases correctly classified,<br />

which determines if the images were properly named,<br />

and (b) the percentage cross-validated grouped cases<br />

correctly classified, that determines if it is possible<br />

to recognize the image as it was labeled. Analyses to<br />

determine the potential impact of background color<br />

on discrimination were also conducted by cropping<br />

the image and placing it on a white background. All<br />

statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 19.0.<br />

Results. From a search of the internet, 703 images<br />

representing 84 species of Paphiopedilum and 214<br />

images representing 25 species of Phragmipedium<br />

were acquired (Tables 1 and 2). This represents 96%<br />

coverage of both genera.<br />

Paphiopedilum. – Cross-validation within sections and<br />

subgenera illustrated that some species were easier<br />

to distinguish than others (Table 3). For example,<br />

Paphiopedilum glaucophyllum and P. liemianum<br />

have broadly similar colors and therefore even<br />

within an analysis of species just from the section<br />

Cochlopetalum, only 18.2% of images of P. liemianum<br />

could be assigned to correct species and in the case<br />

of P. glaucophyllum no images could be placed<br />

within the species. As mentioned this could be due to<br />

the similarity in color of the two species and others

Sanz et al. — Species differentiation using image analysis 166<br />

table 1. A list of species a from the genus Paphiopedilum, taxonomy and the number of images used within the study.<br />

Species Subgenus Section <strong>No</strong>. images<br />

P. acmodontum M.W.Wood Paphiopedilum Barbata 3<br />

P. adductum Asher Paphiopedilum Coryopedilum 4<br />

P. appletonianum (Gower) Rolfe Paphiopedilum Barbata 8<br />

P. aranianum Petchl. Paphiopedilum Paradalopetalum 0<br />

P. argus (Rchb.f.) Stein Paphiopedilum Barbata 11<br />

P. armeniacum S.C.Chen & F.Y.Liu Parvisepalum Parvisepalum <strong>12</strong><br />

P. barbatum (Lindl.) Pfitzer Paphiopedilum Barbata 13<br />

P. barbigerum Tang & F.T.Wang Paphiopedilum Paphiopedilum 5<br />

P. bellatulum (Rchb.f.) Stein Brachypetalum Brachypetalum 6<br />

P. bougainvilleanum Fowlie Paphiopedilum Barbata 7<br />

P. bullenianum (Rchb.f.) Pfitzer, Paphiopedilum Barbata 5<br />

P. callosum (Rchb.f.) Stein, Paphiopedilum Barbata 10<br />

P. canhii Aver. & O.Gruss Paphiopedilum Barbata 3<br />

P. charlesworthii (Rolfe) Pfitzer Paphiopedilum Paphiopedilum <strong>12</strong><br />

P. ciliolare (Rchb.f.) Stein Paphiopedilum Barbata 9<br />

P. concolor (Lindl. ex Bateman) Pfitzer Brachypetalum Brachypetalum 3<br />

P. dayanum (Lindl.) Stein Paphiopedilum Barbata 11<br />

P. delenatii Guillaumin Parvisepalum Parvisepalum 10<br />

P. dianthum Tang & F.T.Wang Paphiopedilum Paradalopetalum 4<br />

P. druryi (Bedd.) Stein Paphiopedilum Paphiopedilum <strong>12</strong><br />

P. emersonii Koop. & P.J.Cribb Parvisepalum Parvisepalum 13<br />

P. exul (Ridl.) Rolfe Paphiopedilum Paphiopedilum 4<br />

P. fairrieanum (Lindl.) Stein Paphiopedilum Paphiopedilum 16<br />

P. fowliei Birk Paphiopedilum Barbata <strong>12</strong><br />

P. gigantifolium Braem Paphiopedilum Coryopedilum 2<br />

P. glanduliferum (Blume) Stein Paphiopedilum Coryopedilum 4<br />

P. glaucophyllum J.J.Sm Paphiopedilum Cochlopetalum 7<br />

P. godefroyae (God.-Leb.) Stein Brachypetalum Brachypetalum 11<br />

P. gratrixianum Rolfe Paphiopedilum Paphiopedilum 10<br />

P. guangdongense Z.J.Liu & L.J.Chen Paphiopedilum Paphiopedilum 0<br />

P. hangianum Perner & O.Gruss Parvisepalum Parvisepalum 8<br />

P. haynaldianum (Rchb.f.) Stein Paphiopedilum Paradalopetalum 5<br />

P. helenae Aver Paphiopedilum Paphiopedilum <strong>12</strong><br />

P. hennisianum (M.W.Wood) Fowlie Paphiopedilum Barbata 6<br />

P. henryanum Braem Paphiopedilum Paphiopedilum 9<br />

P. hirsutissimum (Lindl. ex Hook.) Stein Paphiopedilum Paphiopedilum 9<br />

P. hookerae (Rchb.f.) Stein Paphiopedilum Barbata 16<br />

P. inamorii P.J.Cribb & A.L.Lamb Paphiopedilum Barbata 1<br />

(continues)<br />

LANKESTERIANA <strong>12</strong>(3), December 20<strong>12</strong>. © Universidad de Costa Rica, 20<strong>12</strong>.

168 LANKESTERIANA<br />

table 1. Continues.<br />

Species Subgenus Section <strong>No</strong>. images<br />

P. insigne (Wall. ex Lindl.) Pfitzer Paphiopedilum Paphiopedilum 13<br />

P. javanicum (Reinw. ex Lindl.) Pfitzer Paphiopedilum Barbata 8<br />

P. kolopakingii Fowlie Paphiopedilum Coryopedilum 1<br />