The first artwork in Robert Gober’s long-awaited retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York is a little oil painting of his childhood home in Connecticut, done when he was only 21. It’s a perfectly competent but undistinguished painting, and many other artists would have left such a youthful work out of a major museum survey. Gober hangs it right at the front, because with his art you never leave home. Childhood marks us for life.

The past haunts seemingly empty places, and memories rise up unwilled. Even the echoing galleries of MoMA’s second floor can be transformed into fraught domestic spaces: one white cube is interrupted by a closet door just a little too small, like the bedroom you grew up in, abandoned, but cannot forget.

Over three decades Gober, one of the most powerful but puzzling artists to emerge in 1980s New York, has produced sculptures and drawings that are spare, sad, eccentric and deeply moving – but moving in a way that can be maddeningly hard to explain.

His handmade wax and plaster objects, of disembodied legs or of a flour sack with human breasts, reinscribed personal histories and deep emotion into American sculpture, after decades when the avant-garde disdained anything that smelled of narrative.

What those narratives might say, however, is not so clear. Even this show’s catalogue, scaled more like a novel than the standard museum retrospective doorstop, prefers intimacy to analysis. (It contains, by the way, one of the most beautiful essays on contemporary art I have read in years: a 60-page tour de force by Hilton Als, the New Yorker critic and author of White Girls, that sets Gober’s work amid personal explorations of sexual, racial and religious identity.)

Gober’s most arresting sculptures from the 1980s are plaster sinks, mounted relatively low on the gallery walls. They are not readymades, like Duchamp’s upturned urinal of 1917. They are painstakingly crafted sculptures of sinks, fragile, delicate, from a limbo zone between industrial production and personal craft. Where the faucets should be are only two little holes, and drains are absent too, which turns the sinks into surprisingly anthropomorphic sculptures: a torso with two nipples and a bellybutton, maybe.

They also recall the ablutions of Catholic worship – Gober was an altar boy in his youth – and the suffering of people with HIV/Aids, among them many of Gober’s friends. On a scaffolding outside one of MoMA’s big picture windows, two sink sculptures are half-buried in a grassy knoll, two his-and-his tombstones.

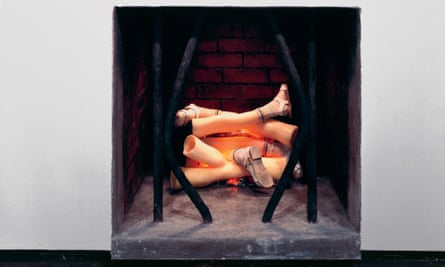

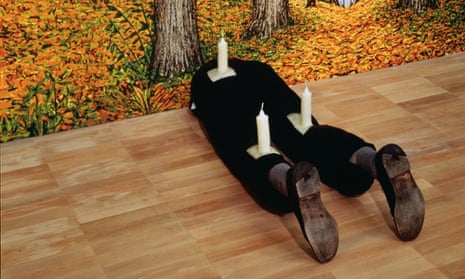

Childhood, sexuality, illness, religion. Gober’s sculptures are sphinx-like but his themes are as big as they come, and they play out, more than anywhere, on the terrain of the human body. By 1989 he was casting beeswax into sculptures of men’s legs, complete not only with shoes and trouser legs but also human hair stuck to the ankles. One pair of legs, lying on the floor, has three fat candles sticking out of them: phallic offerings for the dead. Another is punctured by the drains missing from Gober’s sinks, turning the body into something harrowingly, unhealthily permeable.

This is a sober, unhurried and genuinely affecting exhibition, organized by curators Ann Temkin and Paulina Pobocha in close partnership with the artist. (Gober, for better or worse, has had an awfully evident hand in the hang; not unlike the Jeff Koons show still on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art, this one beatifies a 1980s artist very much on his own terms.)

The exhibit even tames MoMA’s usually inhospitable central atrium, converting it into an ad-hoc chamber covered with a hand-painted mural of a forest. Inside and outside get scrambled, and so does the symbolism of the sinks: the ones here, finally, have running water. There are windows, but they’re barred, like in a prison. Stacked against the walls are yellowing newspapers, the Times and the Post, bearing headlines from 1992: “Vatican Condones Discrimination Against Homosexuals”. A GOP convention featuring Pat Buchanan, Pat Robertson and other “Merchants of Hate”. Legal abortion survives at the supreme court, barely. Dan Quayle’s wife aims to shore up the women’s vote. Woody, Mia, Soon-Yi. And lead in the water supply – fatal.

There is some iffy later sculpture that, it’s hard to deny, descends into pastiche: a new sink whose backboard is metamorphosing into a forest, another in which legs and sink are woven together as warp and weft. A major installation that features a headless Jesus spouting water, and lithographs of the Times from 12 September 2001, feels uncomfortably pat.

But even Gober’s less successful later works display the inscrutable, melancholy force of his best art of the 1980s and 1990s. They imbue familiar forms with unfamiliar weight. They speak a language just beyond our understanding, but which is all the more powerful since we only understand it in parts.

Their political force has not waned either. As a gay critic who came of age after the first phase of the epidemic, I have often looked to Gober’s art as a collection of memento mori, of burning relics from an era when boys like me didn’t know if they’d live another year.

This past July, though, the head of the World Health Organization’s HIV/Aids division warned of “exploding” infection rates among gay men, who remain 19 times more likely than the general population to contract HIV. Seroconversion rates among young gay Americans, particularly, have spiked in the last decade, even with the introduction of pre-exposure prophylaxis (a preventive drug therapy that, in one recent survey, three-quarters of gay men had never heard of). History is fate. Bodies grow and bodies fester. The sink still has no water, and the past will never wash off.

Robert Gober: The Heart Is Not a Metaphor Museum of Modern Art, New York, through January 18, 2015.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion