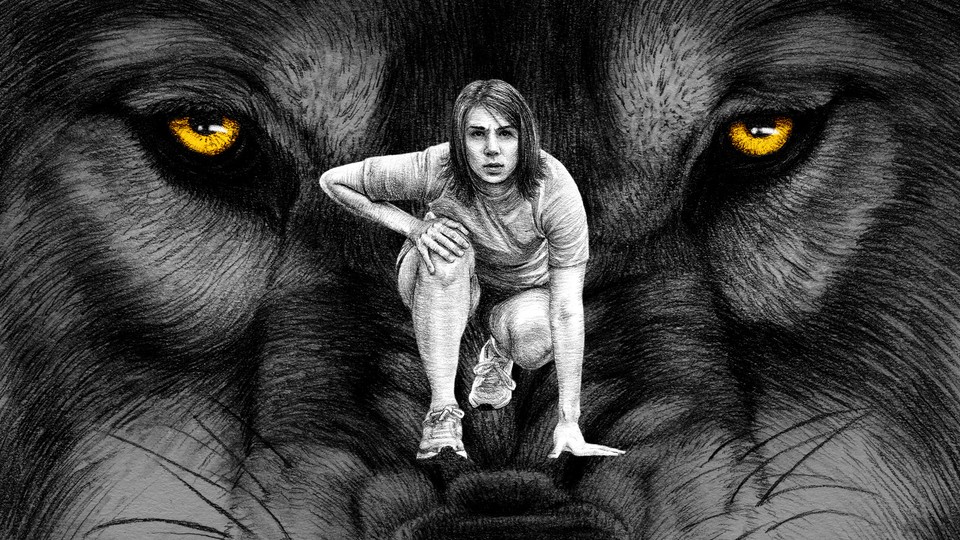

The Book That Teaches Us to Live With Our Fears

Wolfish explores the question of what, exactly, we perceive as threats.

In classic fables and fairy tales, no predator—and perhaps no villain—makes more frequent appearances than the wolf. Greek antiquity gives us the Boy Who Cried Wolf, Little Red Riding Hood famously gets eaten by a wolf, and yet another one blows down the Three Little Pigs’ houses. Wolfish, the writer Erica Berry’s debut, looks both at these invented wolves and at the real ones that have, of late, returned to her home state of Oregon; she also examines the more contemporary wolf metaphors—lone-wolf terrorists, warriors as wolves—that many people use to describe, or perhaps justify, their fear of other humans.

Berry has suffered badly from fear of that “symbolic wolf”—a term she gets from the veterinary anthropologist Elizabeth Lawrence. This is Wolfish’s true subject. Her wolf is a male one, created by a string of disturbing encounters with men and by a lifetime of messages—explicit and subliminal alike—that tell girls and women to perceive men as threats. One of Berry’s projects is dismantling this idea, both to defuse the danger it creates for poor men and men of color and to free herself from the anxiety it creates. She writes of realizing that the “calm I chased on human streets would not come from pepper spray but from metabolizing, and contextualizing, the things that had scared me in the past.”

Among the book’s strengths is Berry’s awareness that, as she puts it, “my wolf is not your wolf.” Berry combines memoir, journalism, and cultural criticism, weaving in others’ voices to remind readers that her perspective is only one of many. For some—such as the writer Cyrus Dunham, who fears not being able to honestly explain their gender identity to others—the wolf represents deceit. For others, the wolf, endangered as it long has been, symbolizes the terrifying destruction that humans have wrought on our environment; a conservationist tells Berry that he is “so worried about our collective future” that he and his wife don’t want to have kids. Berry’s braided approach renders Wolfish both a vulnerable self-investigation and a wide-ranging exploration of fear—and, ultimately, an antidote to it. She makes a stirring case for walking alongside the symbolic wolf.

Wolfish has its share of real animals. Berry devotes one chapter to a childhood wolf sighting—imagined, it turns out, not real—in Yellowstone National Park, and another to a research trip to the UK Wolf Conservation Trust, where wolves unable to live in the wild are kept and cared for. She writes about a cousin in Montana who posed on social media “grinning with a boyfriend as they held up the freshly killed carcasses of what looked like two dead wolves,” and travels to a county in eastern Oregon where a resurgence of wolves has created a furious split between people who want to protect the wolves and people who see conservation projects as a form of government overreach. OR-7, an Oregon-born, radio-collared wolf whose thousand-mile quest for a mate made the news in the early 2010s, appears in nearly every chapter, his trek giving the otherwise sprawling book a measure of shape.

Berry writes evocatively about these real wolves, yet she seems consistently drawn away from the wolves themselves and toward humans’ responses to them. Her writing is richest when she fully commits to examining wolf metaphors and the ways in which we turn even very real wolves into symbols. On a return visit to eastern Oregon, she speaks with a Forest Service ranger who tells her that the wolf-conservation arguments from Berry’s first trip have evolved into broader debates about the role of government in individual lives. “The new wolf is the face mask,” he says. A comparison of wolves to face masks is hardly one of the traditional metaphors Berry set out to investigate, and it seems to fascinate and alarm her in equal measure.

Still, Wolfish focuses primarily on wolf metaphors that have been handed down over time. Berry returns frequently to the story of Little Red Riding Hood, a stand-in for women like herself who have learned to fear predatory male wolves—which is to say, predatory men. A key difference between literal wolves and wolves as metaphors for our fears is that, in general, even wolf-fearing humans know how unlikely they are to be killed by one. As Berry writes, “To call a death by wild wolf a freak accident is almost to understate it.”

By contrast, in Charles Perrault’s version of “Little Red Riding Hood,” which is the basis for most contemporary iterations of the tale, the Big Bad Wolf’s attack is anything but random. Indeed, it is promised, so long as you understand that the wolf is meant to be read as a man, and Little Red as a girl who, by straying from the route to her grandmother’s house, invites that man to attack her. “Perrault’s story,” Berry observes, “is not meant to teach boys. You cannot train a wolf. Only the girl has the lesson to learn. Only the girl can keep herself safe.” Contained in the parable is a regressive notion of female responsibility: It is Little Red’s duty to control and conceal herself, lest her female presence excite a man to violence. Anyone raised as a girl, or around girls, is likely to recognize this idea.

To Berry, the harmfulness of this paradigm—that women are to blame if they suffer male predation—is evident. It generates fear and distrust pervasive enough to stifle not only female sexuality but also the development of female minds. A more difficult question, for her, is whether fear of men is useful. She wishes to consider it “residual from a world that told me I was a victim” and, as a result, does not “want to risk crying wolf.”

Yet Berry cannot silence her sense that Little Red’s story has a “bulb of truth.” On a multiday train ride across the country, a man sits next to her and begins talking, inappropriately and somewhat incoherently, about his ex and his struggles with addiction. When, apprehensive, she moves to a different car, the man brings her a notebook’s worth of hastily written letters suggesting that Berry may be an “evil person” but could potentially still “help [him].” She shows a conductor, who gives her a lockable sleeping car to wait in until the man can be removed from the train. In retrospect, Berry can neither deny the utility of her fear nor decide how valuable it was. Was the man a “lone wolf,” poised for violence? Was he simply lonely and ill? Or was he, like real wolves, a being “that could be both feared and feared for?”

Feminists have long struggled with the question of what male behavior to fear—or, to put it more dramatically, the question of whether women need to be on guard against all men. Berry writes about a childhood friend who, upon hitting puberty, was warned by her mother not to put on makeup or dress nicely if she planned to take public transportation: Doing so would invite attention, the logic went, which was inherently dangerous. Many parents, consciously or not, teach their children such lessons, inviting them to fear the opposite sex, or people of other races or backgrounds, or the world beyond what the parents know. (Consider the extreme example of a recent Curbed piece about Upper East Siders who don’t let their adolescent kids outside alone.)

In Tomorrow Sex Will Be Good Again, the academic Katherine Angel notes that rhetoric that emphasizes fear of the unknown over the potential richness of exploration “doesn’t allow for ambivalence, and it risks making impermissible—indeed dangerous … the experience of not knowing what we want.” Indeed, it turns recipients into 21st-century Little Reds, charged with avoiding the wolf through social savvy and personal knowledge more perfect than that which anyone could reasonably attain.

Berry, like Angel, wants to fight for exploration and ambivalence. She sees them as tools for alleviating fear. Another of her proposed tools is the diminishment of myopia. At the British wolf trust, watching visitors and researchers react to the wolves living there, she sees that to “understand an animal exists neither to kill you nor cuddle you is to untangle your ego from its life—to see it as complex and wild, worthy of existence independent of your feelings about it.” She does not explicitly connect this revelation to how humans might approach one another.

But considering real wolves always brings Berry back to the symbolic one, and considering human responsibility to wild animals helps her reassess our responsibilities to one another. In the case of wolves, we can mitigate danger through land-management strategies that create habitats for both wolves and their natural prey. It isn’t so easy to know how we can mitigate the dangers we pose to other humans, but Berry ends Wolfish resolving to neither ignore her fear nor live in thrall to it—an approach that comes from conservationists’ perspective on wolves. Only by managing and mitigating fear and its causes can we get what Berry truly wants: “a world where we could all stay.”

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.