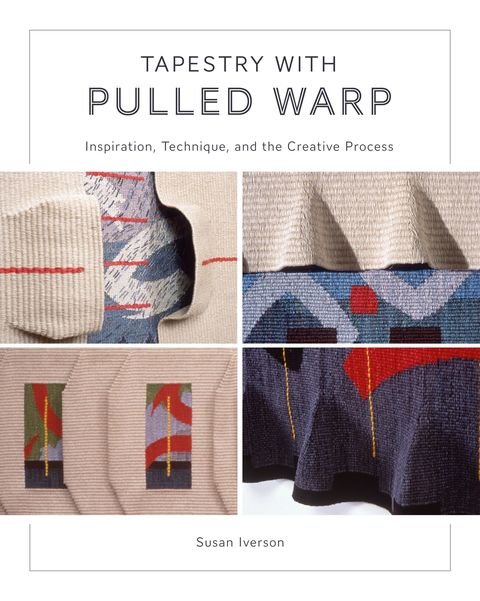

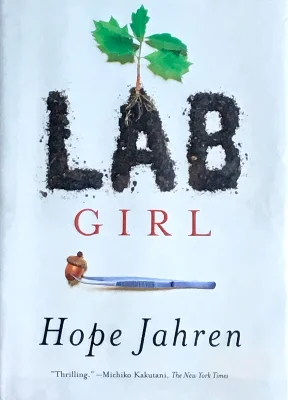

For a very long time, I have been intrigued by the sculptural possibilities of pulled-warp tapestries. Susan Iverson’s new book, Tapestry With Pulled Warp: Inspiration, Technique, and the Creative Process, makes me want to carve out some time to sample and to explore. This book combines clear written instructions with lots of technical images, beginning with how to set up the loom for weaving samples, the materials and tools needed for making patterns and the spacers for inserting into the warp while weaving.

For those of us who tend to work intuitively, heed this statement!

“Always make a pattern for your pulled warp tapestries. This technique can be counterintuitive, so you want to make sure that what you are planning will actually work. The pattern will define all the areas that are to be woven and those that remain unwoven….Your imagination, while wonderful, does not replace a pattern.” pp 20, 22

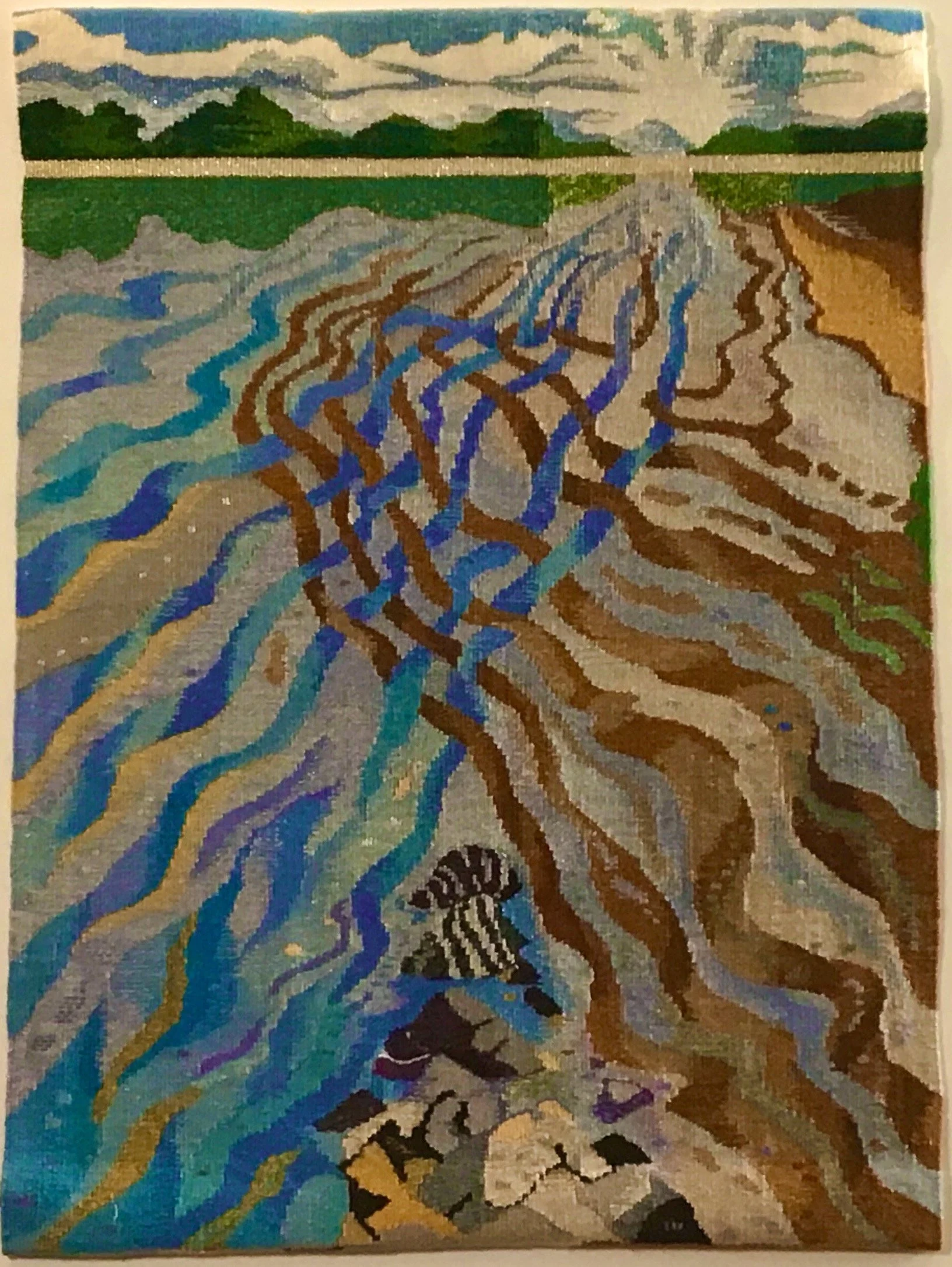

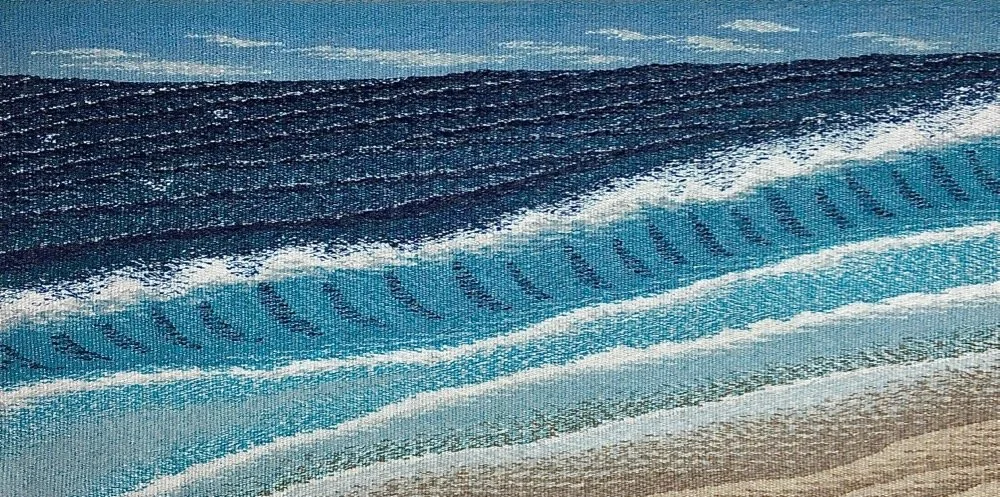

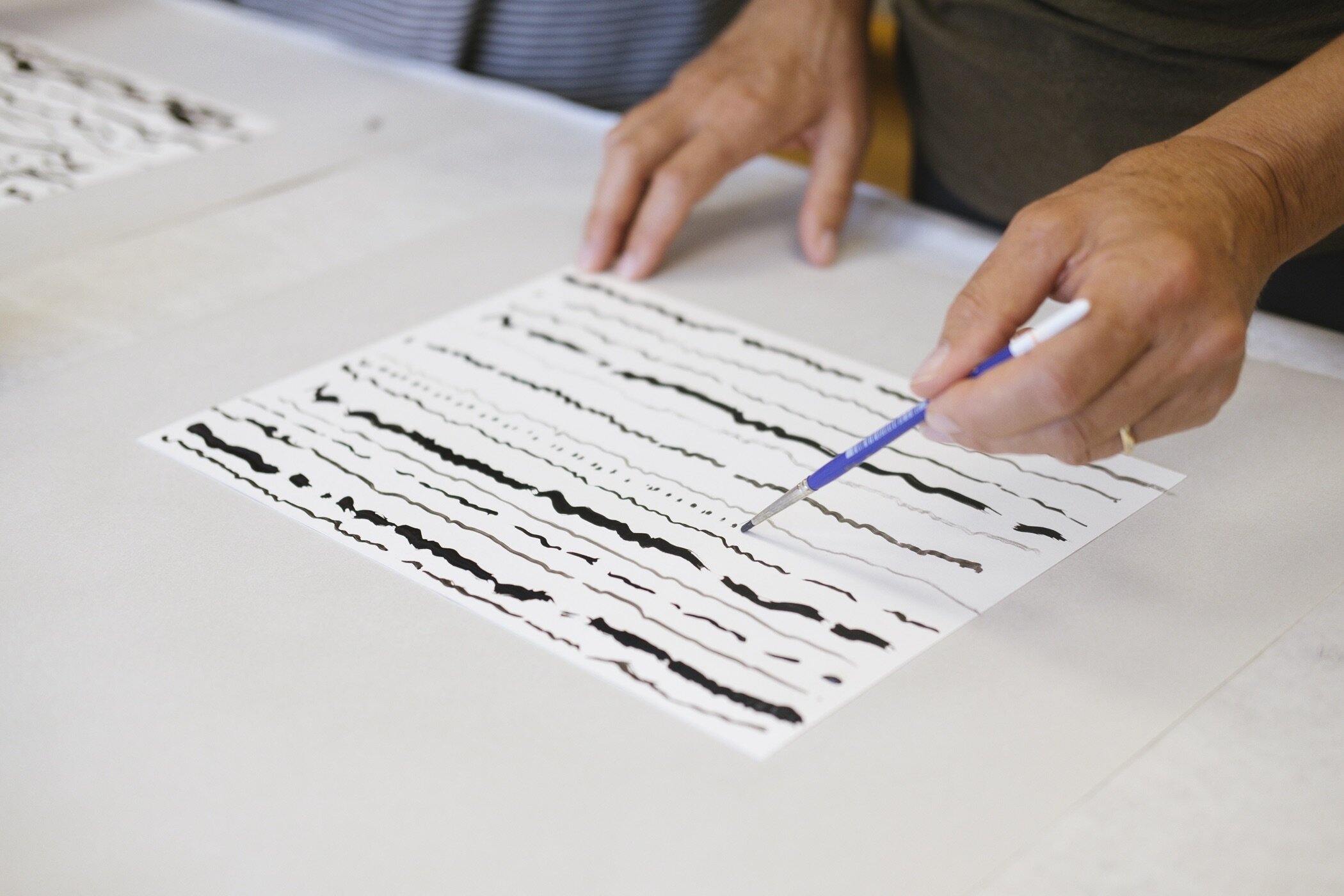

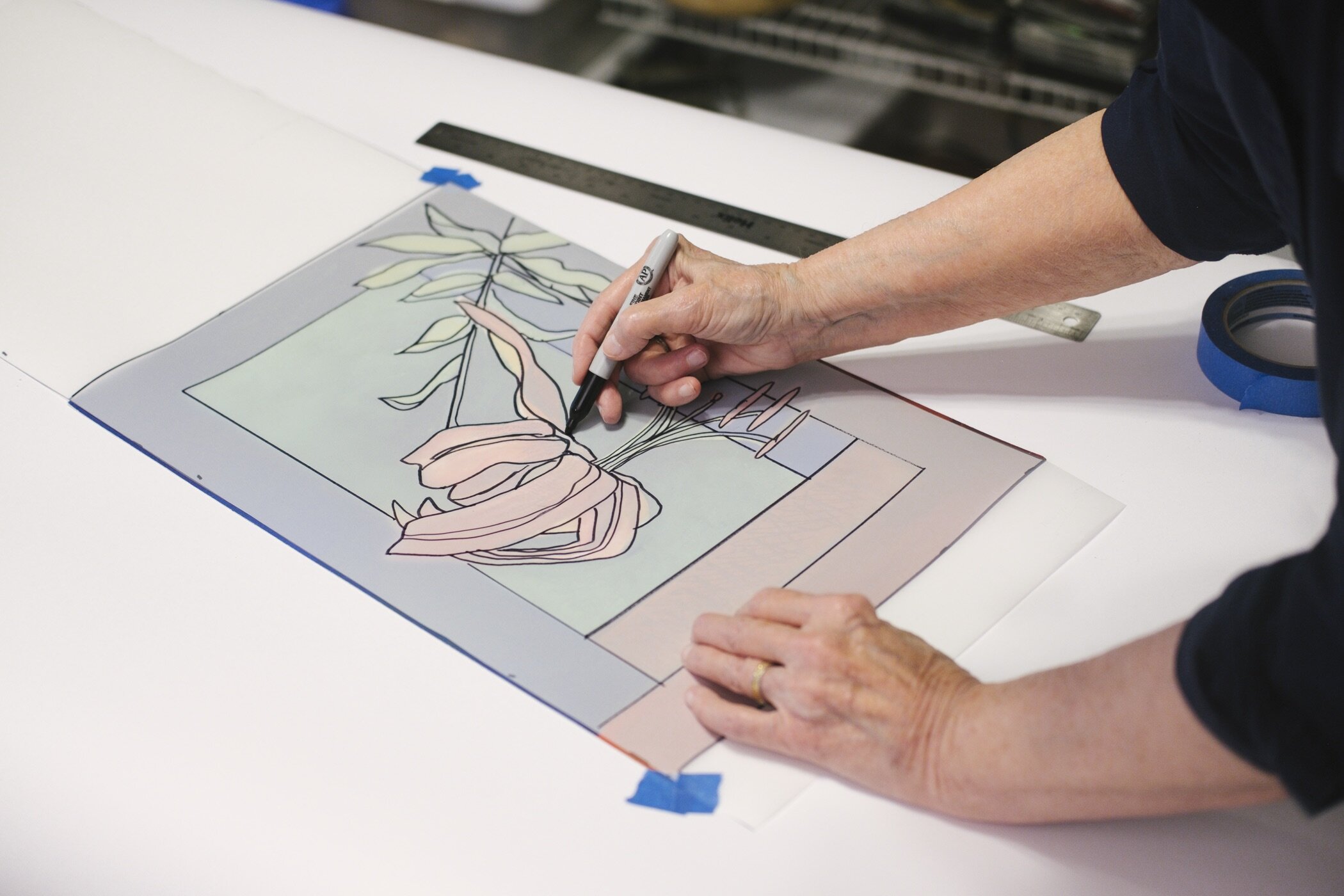

Step-by-step images and instructions provide a clear guide for weaving each sample of flat curves and angles. Once woven and cut from the loom, the moment arrives for pulling of the warps. Again, there is a strategy that requires planning the sequence for doing so.

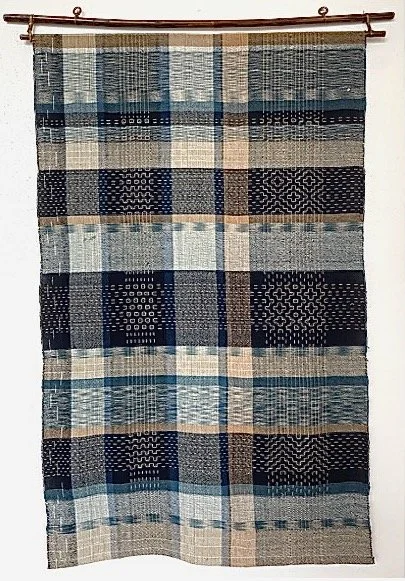

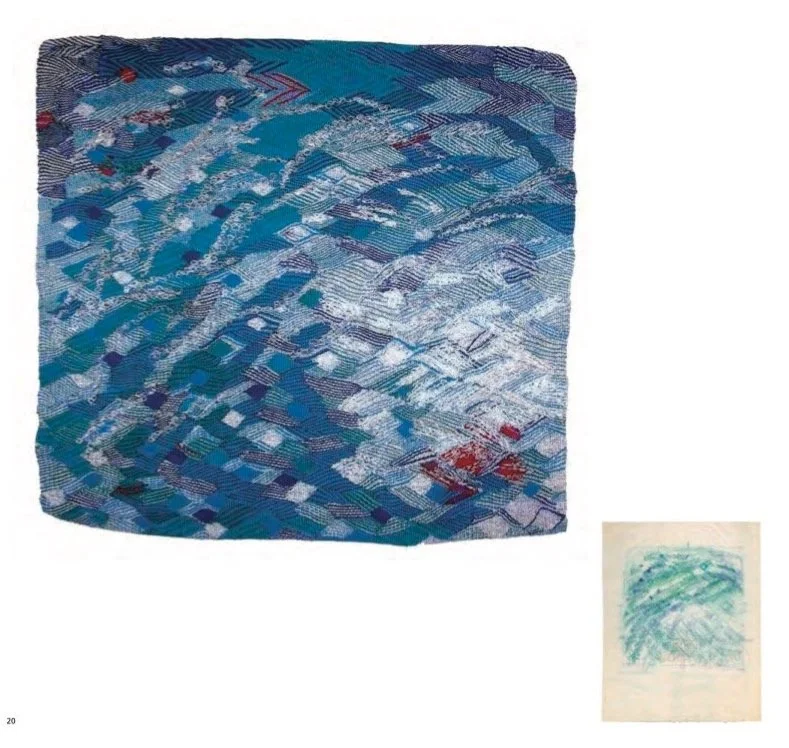

pulled warp tapestry process, photo credit: Edward Parsons (image provided by Schifferbooks)

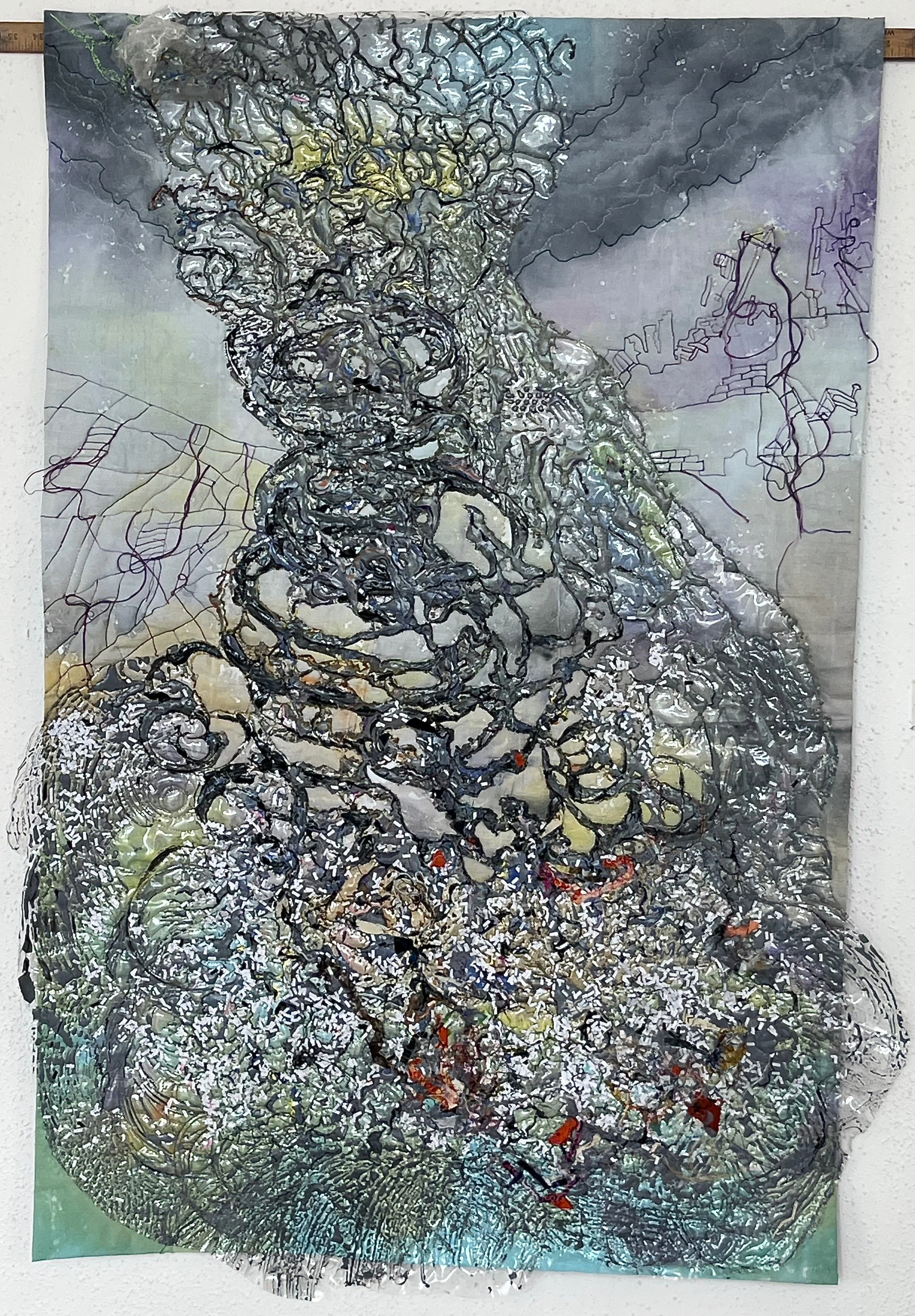

Subsequent chapters cover how to approach planning for three-dimensional forms, such as loops, flaps, ridges and ripples, plus three-dimensional curves and spirals. Here it is essential to make a maquette, in addition to the pattern.

Throughout these chapters, Susan Iverson poses “What If’’ questions, pushing the weaver to consider more and more possibilities for creating variations of shapes through pulled warp. She also shares numerous tips, pitfalls, strategies—all of which are essential to successfully being able to master this approach to tapestry weaving and design.

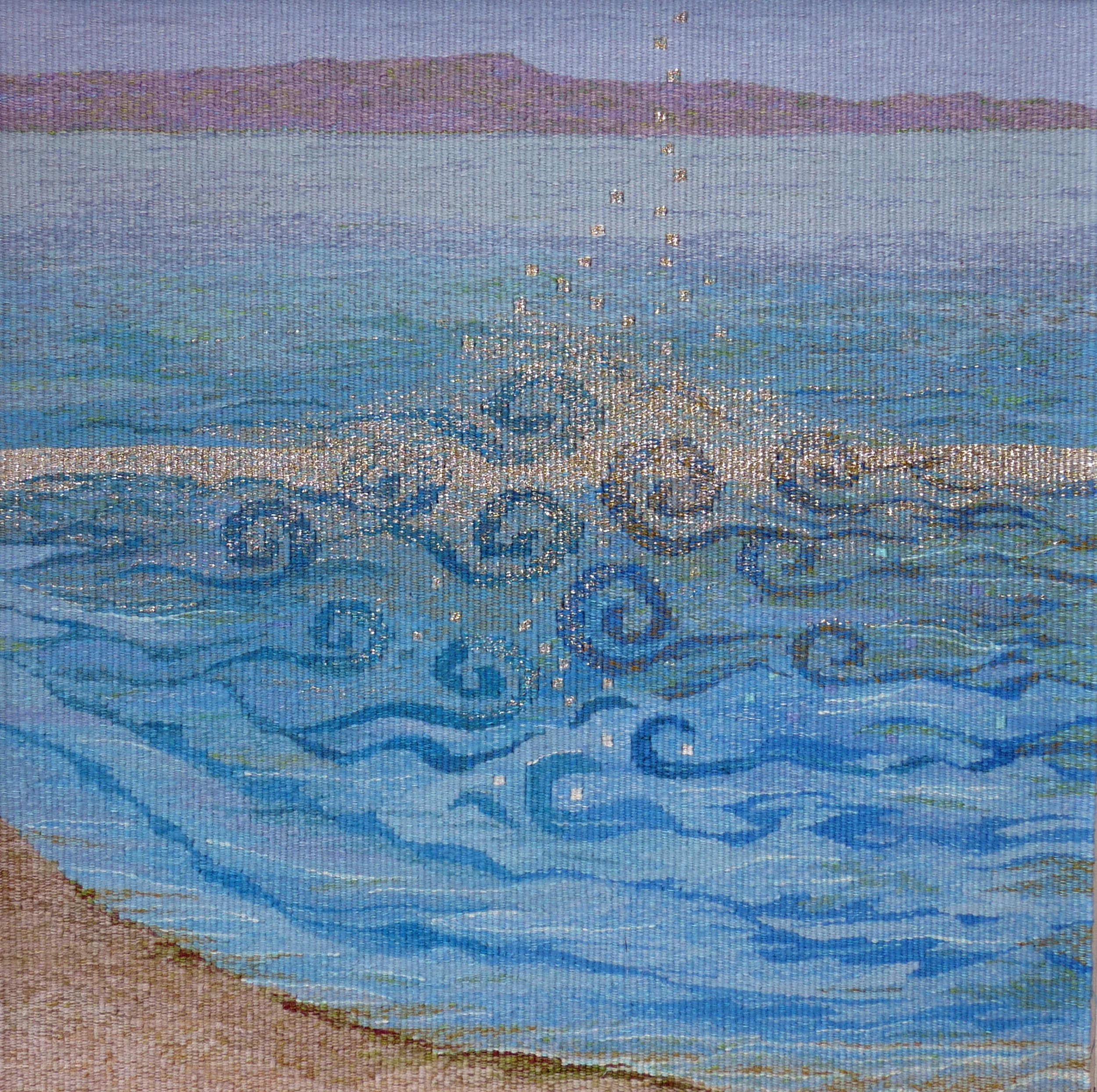

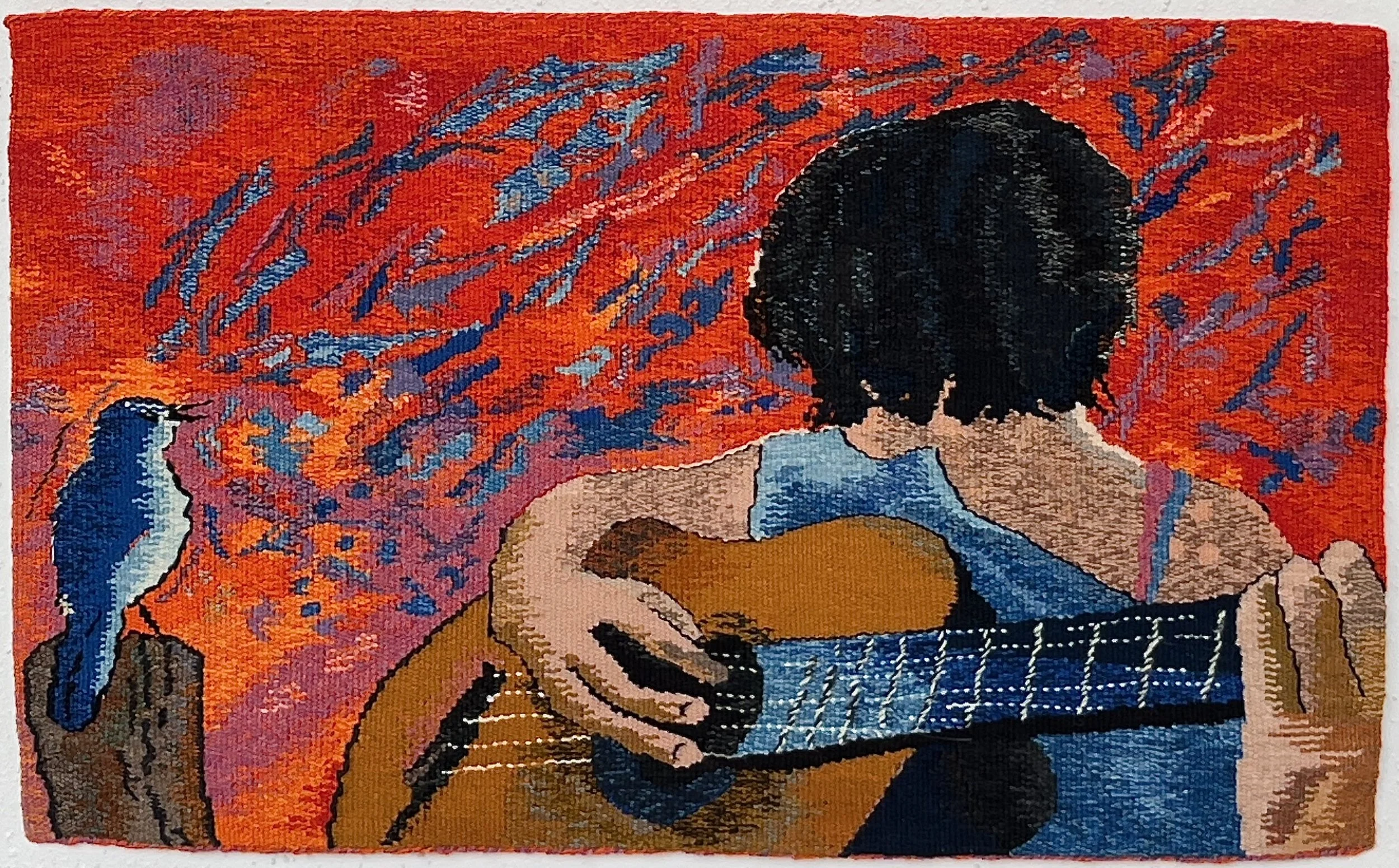

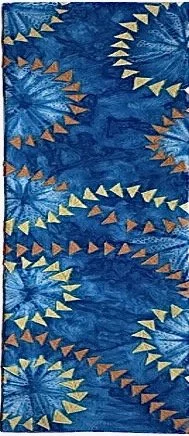

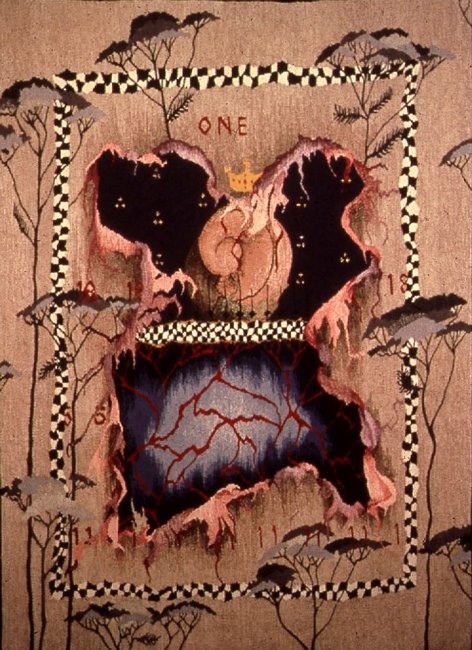

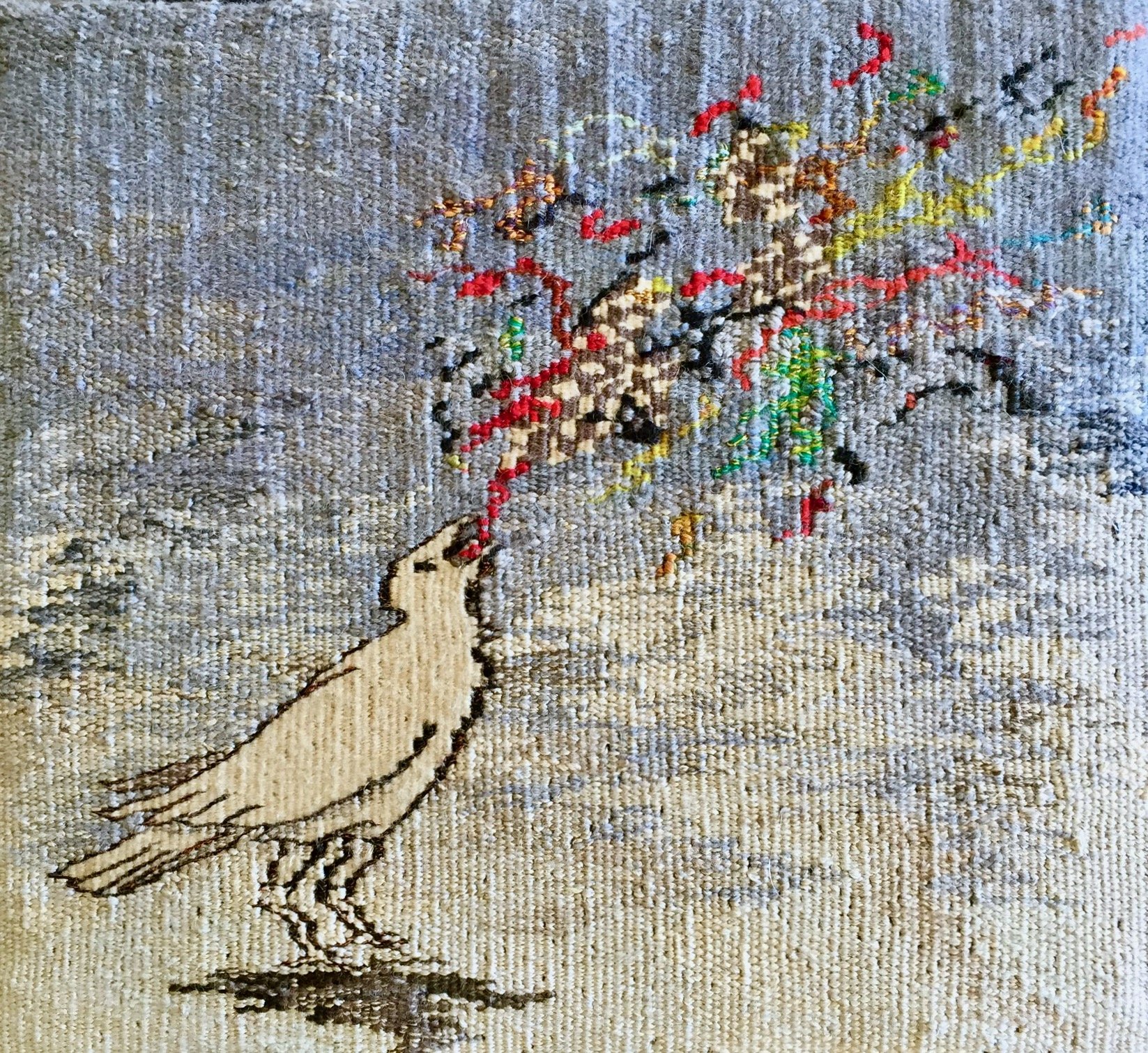

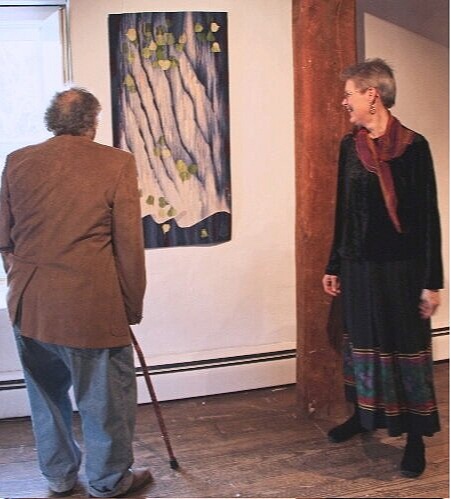

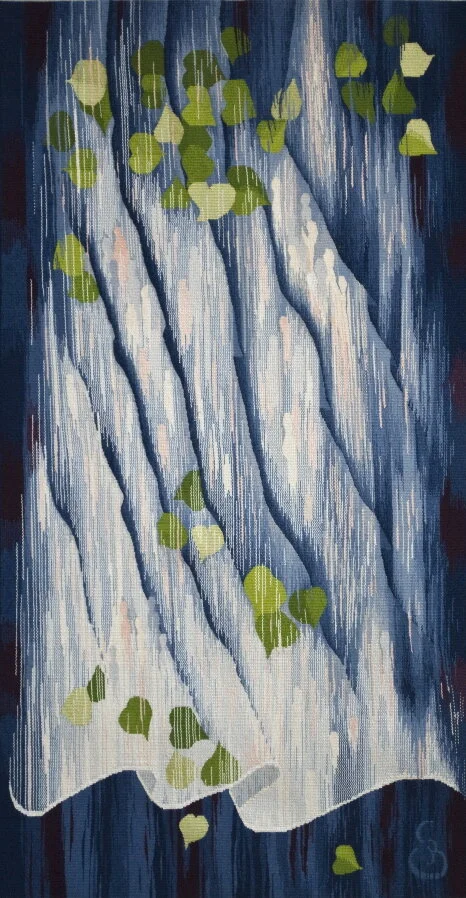

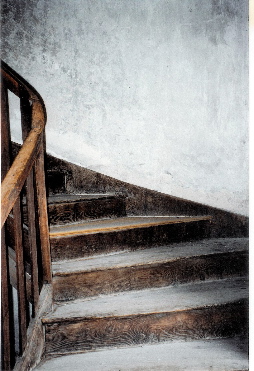

Fleeting (detail) photo credit: Taylor Dabney © Susan Iverson (image provided by Schifferbooks)

The section on “Finishing Solutions” covers how to deal with both the warp and weft ends, as well as mounting solutions for hanging on the wall. Again, there are lots of images showing both the back and front of tapestries.

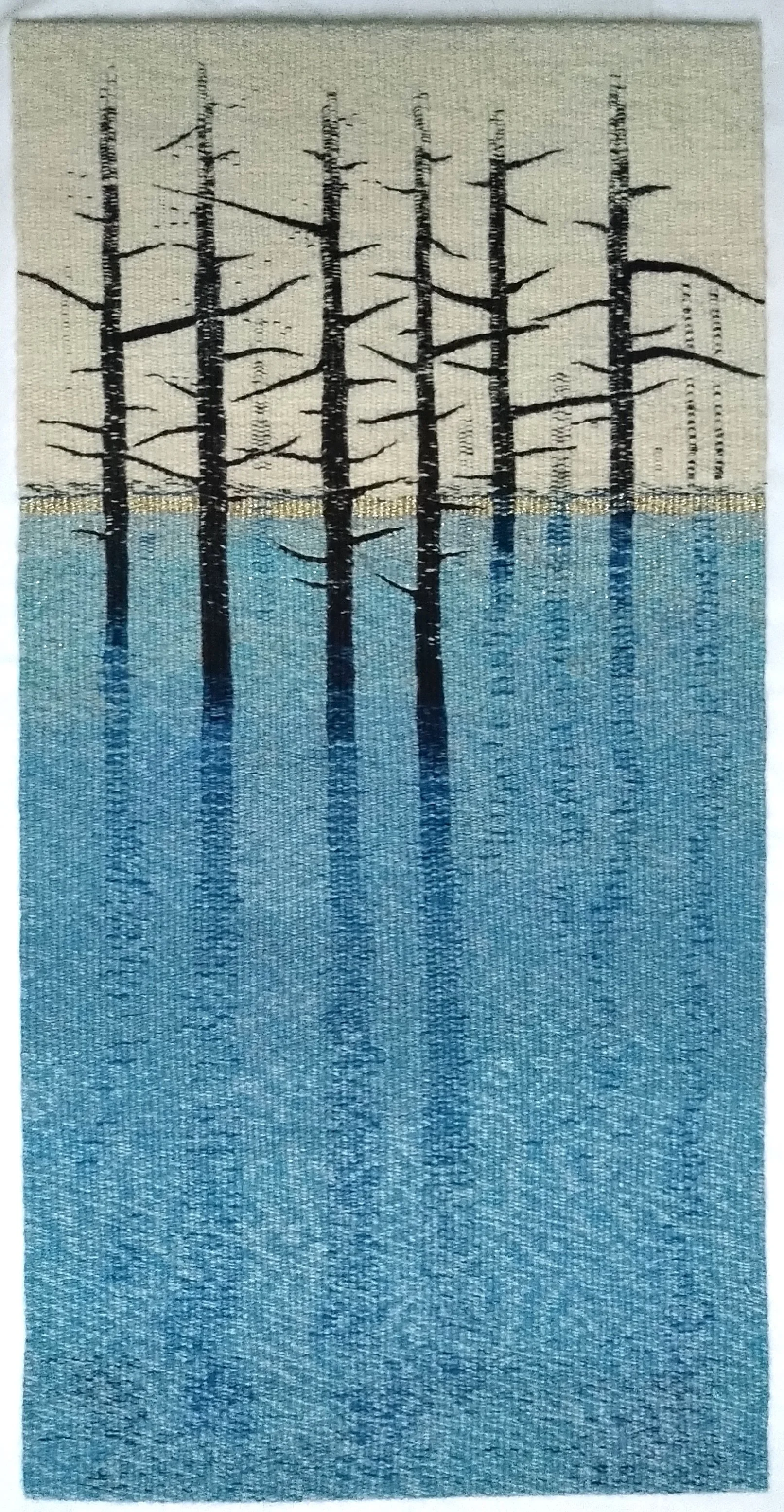

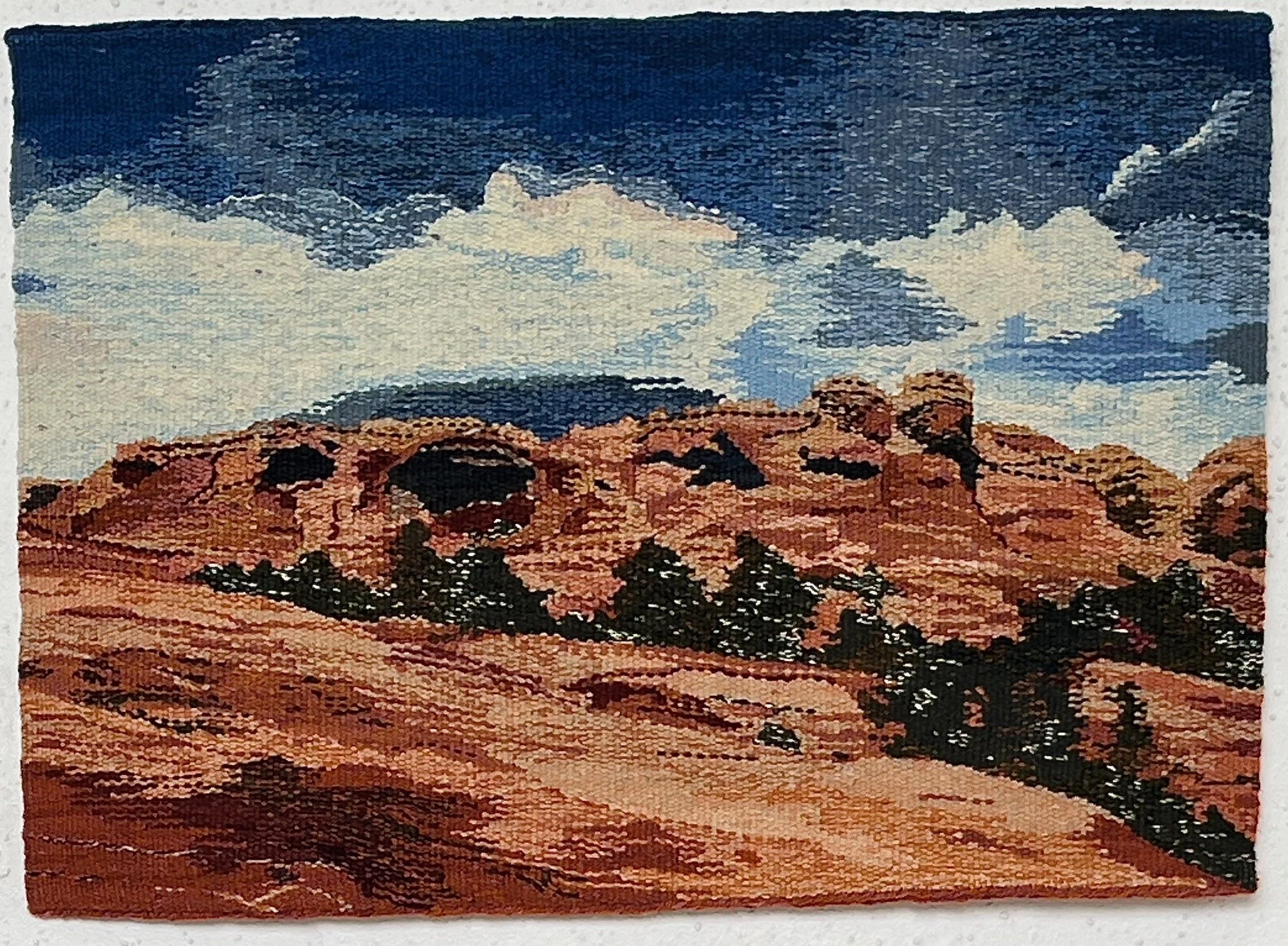

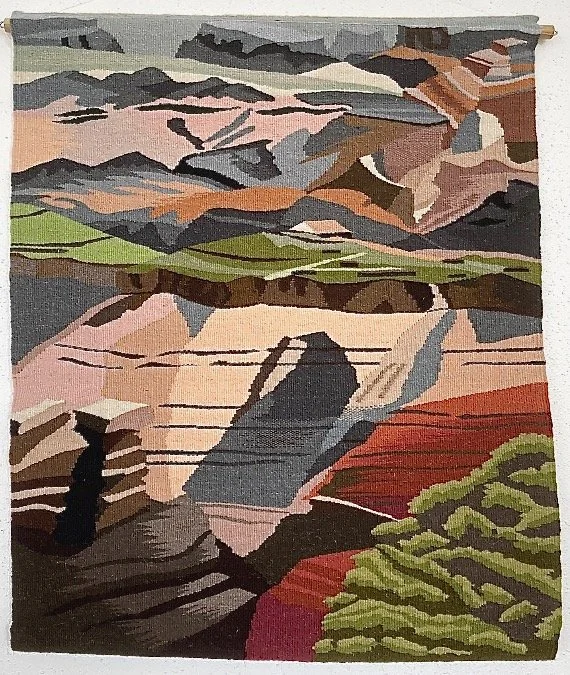

I especially love the section on “Deciding When to Use Pulled Warp (An Artist’s Journey),” where Susan Iverson takes us through the evolution of her works, her thought process and decisions around “why I used pulled warp for certain ideas and not others. Some ideas, generally the more narrative ones, demand to be flat on the wall, while others want to push into space and enhance their physical presence.” (p.108).

This book balances the practical with the vision and creative thought behind when to use pulled warp in tapestries; a must-have guide for anyone wanting to explore the how, why, and when behind creating pulled-warp tapestries.

Pulled Warp Tapestries: Inspiration, Technique, and the Creative Process is available for pre-order through Schiffer Books, and will be released on February 28, 2024.