Chutes, Ladders, and Buckets: What’s Blooming in the Smithsonian Garden’s Orchid Collection

April 23, 2015 at 4:17 pm smithsoniangardens Leave a comment

There are few orchids as unusually delightful and whimsical as the genera Gongora, Stanhopea, and Coryanthes in family Orchidaceae. Largely distributed through the neotropics, these genera are closely related under the subtribe Stanhopeinae. Though they share a similar way of enticing pollinators to visit their flowers, each of these orchids offer something unique as well.

L to R: Gongora aff. quinquenervis, Coryanthes trifoliate, and Stanhopea jenischiana from the Smithsonian Gardens Orchid Collection

Gongora, Stanhopea, and Coryanthes all attract euglossine bees to pollinate their blooms by producing highly aromatic oils on their flowers. Male euglossine bees, drawn by the intense fragrance, land on the flowers, scrape up the scented oil, and then collect it in spongy pouch-like structures on their back legs. It is believed that the male bees use this behavior is to help attract mates. The more complex the aroma compounds a male bee creates by visiting multiple flowers, the more attractive he appears to female bees.

Transferring collected oils onto its back legs requires a male euglossine bee to release its grip on a flower momentarily. Rather amazingly, these three genera of orchids have each developed a way to capitalize on this moment of vulnerability. Gongoras and Stanhopeas orchids use a “slide” structure formed from the petals and dorsal sepal of each bloom to guide the upside-down tumbling bee past the pollen on the end of the column and out of the flower. It’s nature’s version of “Chutes and Ladders!”

Coryanthes or Bucket Orchids, on the other hand, trap their bee visitors in liquid pooled in the bucket-shaped lip of their flowers. With its wings submerged, a male bee must exit out back of the bucket and past the column containing the pollen to escape the flower. In the process pollen from the flower attaches to the bee’s back. Since this is a traumatic experience, the bee temporarily avoids similar flowers. Eventually, the bee forgets the experience and falls into the same trap on another flower. The pollen already attached to its back then is deposited in the appropriate place on the flower’s column before new pollen adheres to the bee. Unbelievable, right?

Although flower spikes in all three species extend and hang pendulant from the base of the psuedobulbs, the more interesting phenomenon is that all three develop inverted flowers. This adaptation guides the fall of the visiting bee downwards through each orchid’s respective structure to help pollinate the plant.

Though similar in many ways, each genus exhibits a radically different shape. Below is a photo of Gongora aff. quinquenervis from the Smithsonian Garden Orchid Collection. The flower shape is fairly representative of the Gongora genus as a whole and makes for a great model to understand the pollination process. Some say Gongora tend to look like a bird or insect in flight because of its wing-like reflexed lateral sepals. What strikes me in this particular species, however, is its jaggedness and the small barbs coming off the lip. The barbs remind me of a fishing hook with a lure. Considering how the flower uses its structure to attract a pollinator, it’s actually not a bad analogy

Stanhopea jenischiana, most recognizable for the dark eye spots on its yellow lip (see below), pollinate very similarly to Gongoras via a “slide” method. The fall bees experience after entering the flower led these orchids to be nicknamed “Fall-Through” Orchids.

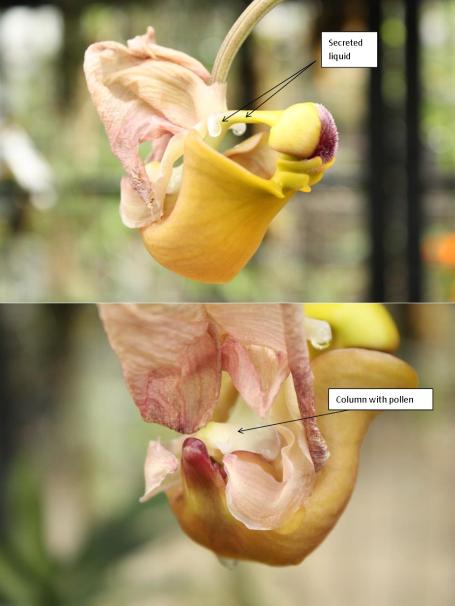

And finally, below is Coryanthes trifoliata. Though the lateral sepals unfortunately are past their peak in this photo, the bucket lip is still intact and shows off some this bloom’s stunning detail! Notice the liquid dripping into the flower’s bucket. The second image shows more clearly the channel through which the orchid forces visiting bee to escape.

While these fantastic orchids abound in the Smithsonian Gardens greenhouses, a few have made their way into the Orchids: Interlocking Science and Beauty at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History over the past several months. Have you had a chance to see any of them? With the show closing this Sunday, April 26 there’s still time to see a few new additions including a Gongora! Don’t miss them!

– Alan M., Smithsonian Gardens Orchid Exhibition Intern

Entry filed under: Collections, Exhibits, Orchids. Tags: orchids.

Trackback this post | Subscribe to the comments via RSS Feed