Click to enlarge. I found this glowing wing of a Morpho butterfly on the entrance trail. Probably it was eaten by a jacamar , a bird with a long tweezer-like beak. These catch butterflies and beat their bodies against a stick until the wings come off. Lou Jost/EcoMinga.

A couple of weeks ago I made a short visit to our lowest-elevation reserve, the Rio Anzu Reserve (1100-1200m elevation) in the Amazon basin, to mark some special orchids for a visiting student to study. Lowland Amazonia is the richest habitat on earth for birds and trees, and also hosts a seemingly never-ending parade of crazy insects. A trip to this reserve is always a mind-boggling experience, even though the reserve is very small and lacks larger birds and diurnal mammals due to indigenous hunting pressure in the surrounding area. (However, black jaguars stalk this forest unseen by human eyes, but recorded in several different camera traps…)

Click to enlarge. A large ant with frightening jaws walked across the morpho wing while I was photographing. Lou Jost/EcoMinga.

For a minute or two I saw this Fulvous Shrike-tanager (Lanio fulvus), a core species of mixed-species insectivorous bird flocks here. Lou Jost/ EcoMinga.

Quite often at the trail entrance of this reserve there will be a big mixed flock of mostly-insectivorous birds scouring the branches and leaves of the forest. On this trip I met with the flock as soon as I got out of the taxi-truck that brought me there. The flock and I seemed to follow the same forest path for a long way, and I enjoyed their noisy company. A particularly sharp bird call alerted me to the “leader” of the flock, a Fulvous Shrike-tanager (Lanio fulvus) an uncommon bird which does not occur at our higher elevation reserves. This is one of the famous “liar” birds (not to be confused with Lyre-birds!) that watches for hawks, etc, and warns mixed flocks of danger, but will sometimes “freeze” the flock with a false alarm call when it sees a bird flush a particularly appetizing insect. It then grabs the insect for itself (Munn 1986). In spite of its occasional duplicity, the presence of this species allows the other flock members to find more food, since they don’t have to waste as much time looking around for danger (they rely on the Shrike-tanager to do that). So a flock will generally cluster around the local pair of Shrike-Tanagers, and they move together through the forest.

This Heliconius butterfly sat on the trail in the Rio Anzu reserve. Photo: Lou Jost/EcoMinga.

Throughout the day fancy butterflies filled the air. My favorite (at least on this day) are the Heliconius butterflies. These butterflies have larva that feed on poisonous passionflower (Passiflora sp.) leaves, and they themselves thus become poisonous to birds. The adults have strong warning colors and patterns, which show a very complex but interesting geographical variation. In any given area, often two different Heliconius species will share exactly the same pattern, but in a different region, the same two species can share a completely different pattern. The geographical variants are intensely studied to give clues about the process of incipient speciation, the possible locations of wet “refugia” during past hot dry epochs, etc. I saw many species that day, but only managed to photograph one.

Passionflower in the forest understory. Photo:Lou Jost/EcoMinga.

Appropriately I soon found a giant passionflower plant nearby. This species is a canopy liana but has specialized short clambering flowering stems that often come out near the ground. They are pollinated by hummingbirds.

The crown of white pointy “tentacles” in the center of the flower have an important function. Flowers that attract hummingbirds generally produce a lot of nectar, and this nectar is a tempting resource for other creatures, including many that play no role in pollination. Flowers with better defenses against nectar robbery will leave more descendants than those that don’t, so very elaborate defenses have evolved in many hummingbird flowers, including this one. The white spikes protect the nectar below them. They are easily parted by a hummingbird’s needle-like beak, but a clumsy ant or bee can’t get its head close to the nectar.

The back of the flower also has a defense against nectar robbers. The bracts surrounding the base of the flower have “extrafloral nectaries”, glands that produce a bit of nectar themselves. Ants and wasps like to hang out there and drink this nectar, and these nasty bugs scare away other kinds of bugs that could chew through the back to get to the big store of nectar inside.

Blue-headed grasshoppers were common on the trail. Click to enlarge. Lou Jost/EcoMinga.

The day was full of grasshoppers. I photographed an especially flashy one, but many more escaped my lens. One of the grasshoppers I did manage to photograph was carrying two parasitic mites (ticks) on one leg. Mites are commonly seen on insects in the tropics, but I don’t know much about them.

Mites (one healthy, one dead) on a grasshopper’s leg in the Rio Anzu. Photo: Lou Jost/EcoMinga.

Along with the grasshoppers were many katydids. Most North American katydids eat leaves, but in the tropics things are more complicated. I found a nasty carnivorous katydid munching the severed torso of a walking stick [male of the genus Oreophoetes, according to Yannick Bellanger’s Comment below], while the walking stick’s mate another walking stick [possibly a new species according to Yannick Bellanger’s Comment below] sat and watched, motionless. The juices of the half-eaten walking stick, in turn, attracted tiny gnats which gathered under the katydid’s head waiting for a chance to steal a mouthful. It was a miniature Serengeti. The annoyed katydid repeatedly swatted the gnats with its forelegs, just like I was swatting the slightly larger gnats that were bugging me. [Edited Dec 1 to reflect my growing doubts that these two walking sticks really belong to the same species. They seem too different from each other. Any experts out there with an informed opinion? Edit June 22 2016: Thanks Yannick Bellanger for the IDs and for answering this question in the Comments. Both are males, of different genera.]

I found this carnivorous katydid munching on a walking stick while the walking stick’s mate another walking stick looks on. Photo: Lou Jost/EcoMinga.

Victim’s head. Photo: Lou Jost/EcoMinga.

Note the complex foot pads of the killer katydid. Click to enlarge. Photo: Lou Jost/EcoMinga.

This walking stick looked on while the katydid ate the other one Photo: Lou Jost/EcoMinga.

After a couple of hours I reached the Rio Anzu itself, an easy 15-minute walk if I had ignored the interesting bugs. This is where the ladyslipper orchid Phragmipedium pearcei grows on the wet riverside limestone. The plants are often submerged when the river rises. On this day the river was low and there were many individuals in flower.

A ladyslipper orchid, Phragmipedium pearcei, on the limestone of the Rio Anzu. Photo: Lou Jost/EcoMinga.

The Rio Anzu. Lou Jost/EcoMinga.

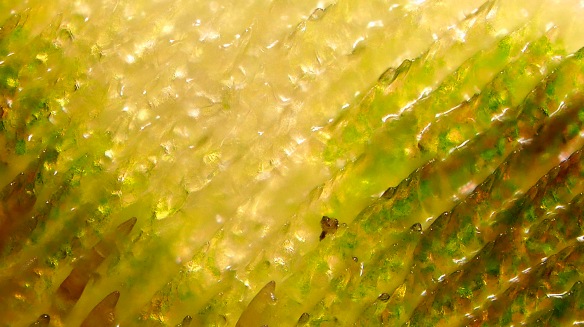

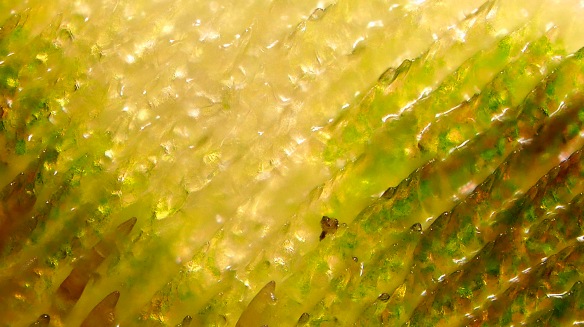

At first glance the texture of this ladyslipper orchid flower is unremarkable. It looks smooth like any other flower. I had never given it a second look until that day. A microscope revealed that the flower was a complex mosaic of textures, hairs, glands and stuff I still don’t understand. The hairs were clearly guides for the insect pollinators, which must first land on the white flat rim of the orchid’s pouch or “slipper” (the pouch is called the “lip” in orchid terminology). This white rim has a row of random green spots, and another loosely organized row of larger brown spots. When magnified, the green spots turn out to be many long parallel dark green ridges, separated by greenish brown “valleys”. The effect is almost iridescent. Edit Dec 1: In response to Lisa’s question below, I did some research and found that the pollinator is a female fly that thinks these green spots are actually aphids, the prey of the fly larvae. The female lands on the flower to lay eggs among the “aphids”, and falls into the pouch. My speculations about the spots looking like fly eyes were wrong.

Top view of the “slipper” or lip of the ladyslipper orchid Phragmipedium pearcei. Lou Jost/EcoMinga.

The staminode above the “slipper” or lip. At this magnification the green spots on the lip begin to show their true complexity. Lou Jost/EcoMinga.

Under higher magnification the green spots on the lip reveal complex textures and stiff hairs. Lou Jost/EcoMinga.

Remarkably complex surface details of the green spots. Lou Jost/EcoMinga.

Closer view of the green spots reveal they are not just smooth spots of color. Lou Jost/EcoMinga.

Eventually the pollinator must fall into the pouch (perhaps drugged by the orchid). Once the pollinator enters the pouch, it finds itself trapped, with limited ways out. Most of the inner surface of the lip is only lightly hairy, but one strip is carpeted with long hairs, and this strip leads the insect up to an escape route that passes directly under the stigma and anthers. The insect thus is forced to pollinate the flower if it wants to get out of there.

A cross-section view of the “slipper”. Lou Jost/EcoMinga.

Closer cross-sectional view. Note the various kinds of hairs. Lou Jost/EcoMinga.

The variety of textures on this flower make me eager to look more closely at other flowers. Expect to see many more micro-photos here in the future!

A jumping spider watched me photographing the grasshoppers. Photo: Lou Jost/EcoMinga.

Lou Jost

EcoMinga

Munn, C. A. 1986. Birds that ‘cry wolf.’ Nature 319: 143-145.

Una breve caminata en nuestra Reserva Río Anzu

IMG – Click para agrandar. Encontré esta ala brillante de una mariposa Morpho en el sendero de entrada. Probablemente fue comida por un jacamar, un ave con un pìco largo en forma de pinza. Estos atrapan mariposas y golpean sus cuerpos contra un palo hasta que se les caen las alas. Fotografía: Lou Jost/EcoMinga

Un par de semanas atrás hice una corta visita a nuestra reserva de menor elevación, la Reserva de Río Anzu (1100 – 1200 m de elevación) en la cuenca del Amazonas, para marcar algunas orquídeas especiales para que un estudiante visitante las estudie. La Amazonía de las tierras bajas es el hábitat más rico del mundo para pájaros y árboles, y también alberga un desfile aparentemente interminable de insectos locos. Un viaje a esta reserva es siempre una experiencia alucinante, incluso aunque la reserva sea muy pequeña y carezca de grandes mamíferos diurnos debido a la presión de la caza indígena en el área circundante (Sin embargo, los

jaguares negros acechan este bosque sin ser vistos por los ojos humanos, pero registrados en varias trampas de cámara diferentes…)

IMG – Click para agrandar. Una hormiga grande con mandíbulas aterradoras cruzó el ala morfo mientras yo estaba fotografiando. Lou Jost/EcoMinga

IMG – Por un minuto o dos vi este Fulvous Shrike-tanager (Lanio fulvus), una especie central de bandadas de aves insectívoras de especies mixtas aquí. Lou Jost/EcoMinga

Muy a menudo, en la entrada del sendero de esta reserva habrá una gran bandada mixta de aves, en su mayoría insectívoras, recorriendo las ramas y hojas del bosque. En este viaje me encontré con el rebaño apenas salí del taxi-camión que me traía allí. El rebaño y yo parecíamos seguir el mismo camino del bosque durante un largo camino, y disfruté de su ruidosa compañía. Un canto de pájaro particularmente agudo me alertó sobre el “líder” de la bandada, un Alcaudón-tangara (Lanio fulvus), un ave poco común que no se encuentra en nuestras reservas de mayor elevación. Este es uno de los famosos pájaros “mentirosos” (¡que no debe confundirse con los pájaros lira!) que vigila a los halcones, etc., y advierte a las bandadas mixtas del peligro, pero a veces “congela” la bandada con una llamada de falsa alarma cuando ve a un pájaro arrojar un insecto particularmente apetitoso. Luego agarra el insecto por sí mismo (Munn 1986). A pesar de su duplicidad ocasional, la presencia de esta especie permite que los demás miembros de la bandada encuentren más comida, ya que no tienen que perder tanto tiempo buscando peligros (dependen del Alcaudón-tangara para hacer eso). Entonces, una bandada generalmente se agrupa alrededor de la pareja local de Alcaudón-Tangaras, y se mueven juntas a través del bosque.

IMG – Esta mariposa Heliconius se sienta en el camino en la Reserva Río Anzu. Fotografía: Lou Jost / EcoMinga

A lo largo del día, elegantes mariposas llenaron el aire. Mi favorita (al menos en este día) son las mariposas Heliconius. Estas mariposas tienen larvas que se alimentan de hojas venenosas de pasiflora (Passiflora sp.), y por lo tanto, ellas mismas se vuelven venenosas para las aves. Los adultos tienen colores y patrones de advertencia fuertes, que muestran una variación geográfica muy compleja pero interesante. En cualquier área dada, a menudo dos especies diferentes de Heliconius compartirán exactamente el mismo patrón, pero en una región diferente, las mismas dos especies pueden compartir un patrón completamente diferente. Las variantes geográficas se estudian intensamente para dar pistas sobre el proceso de especiación incipiente, las posibles ubicaciones de “refugios” húmedos durante épocas pasadas de calor seco, etc. Vi muchas especies ese día, pero sólo logré fotografiar una.

IMG – Flor de la pasión en el sotobosque. Fotografía: Lou Jost / EcoMinga.

Apropiadamente encontré una pasiflora gigante cerca. Estas especie es una liana de dosel pero tiene tallos florales cortos y trepadores especializados que a menudo salen cerca del suelo. Son polinizados por colibríes.

La corona de “tentáculos” puntiagudos en el centro de la flor tiene una función importante. Las flores que atraen colibríes generalmente producen un montón de néctar, y este néctar es un recurso tentador para otras criaturas, incluyendo muchas que no desempeñan ningún papel en la polinización. Las flores con mejores defensas contra el robo de néctar tendrán más descendientes que las que no, por lo que se han desarrollado defensas muy elaboradas en muchas flores de colibrí, incluida esta. Las espigas blancas protegen el néctar debajo de ellas. Se separan fácilmente con el pico en forma de aguja de un colibrí, pero una hormiga o abeja torpe no puede acercar la cabeza al néctar.

La parte posterior de la flor también tiene una defensa contra los ladrones de néctar. Las brácteas rodean la base de la flor tienen “nectarios extraflorales”, glándulas que producen por sí mismas un poco de néctar. A las hormigas y avispas les gusta pasar el rato y beber este néctar, y estos desagradables bichos ahuyentan a otros tipos de bichos que podrían morder la espalda para llegar a la gran reserva de néctar que hay en el interior.

IMG – Los saltamontes de cabeza azul eran comunes en el camino. Click para agrandar. Lou Jost / EcoMinga

El día estuvo lleno de saltamontes. Fotografié una especialmente llamativa, pero muchas más escaparon de mi lente. Uno de los saltamontes que logré fotografiar llevaba dos ácaros parásitos (garrapatas) en una pierna. Los ácaros se ven comúnmente en insectos en los trópicos, pero no sé mucho sobre ellos.

IMG – Ácaros (uno sano, otro muerto) en una pierna de saltamontes en el Río Anzu. Fotografía: Lou Jost/EcoMinga

Junto con los saltamontes había muchos saltamontes longicornios. La mayoría de los saltamontes longicornios norteamericanos comen hojas, pero en los tropicos las cosas son más complicadas. Encontré un saltamontes carnívoro desagradable masticando el torso cortado de un bastón [macho del género Oreophoetes, de acuerdo al comentario de Yannick Bellanger a continuación] se sentó y miró, sin emoción. Los jugos del bastón a medio comer, a su vez, atraían a pequeños mosquitos que se reunían bajo la cabeza del saltamontes esperando la oportunidad de robar un bocado. Fue un Serengeti miniatura. El saltamontes longicornio molesto golpeó repetidamente a los mosquitos con sus patas delanteras, al igual que yo estaba aplastando a los mosquitos un poco más grandes que me molestaban. [Editado el 1 de diciembre para reflejar mis crecientes dudas de que estos dos bastones realmente pertenezcan a la misma especie. Parecen demasiado diferentes entre sí. ¿Algún experto con una opinión informada? Edición 22 de junio de 2016: Gracias Yannick Bellanger por las identificaciones y por responder a esta pregunta en los comentarios. Ambos son machos, de diferente género]

IMG – Encontré este saltamontes longicornio masticando un bastón mientras el compañero del bastón mira otro bastón. Fotografía: Lou Jost/EcoMinga.

IMG – Cabeza de la víctima. Fotografía: Lou Jost/EcoMinga

IMG – Tenga en cuenta las complejas almohadillas de los pies del saltamontes asesino. Click para agrandar. Fotografía: Lou Jost/EcoMinga

IMG – Este bastón miraba mientras el saltamontes se comía al otro. Fotografía: Lou Jost/EcoMinga

Después de un par de horas alcancé el Río Anzu por si mismo, una caminata fácil de 15 minutos si he ignorado los insectos interesantes. Aquí es donde la orquídea zapatito Phragmipedium pearcei crece sobre la caliza húmeda de la ribera. Las plantas a menudo sumergidas cuando el río crece. En este día, el río estaba bajo y había muchos individuos en flor.

IMG – Una orquídea zapatito, Phragmipedium pearcei, en la caliza del Río Anzu. Fotografía: Lou Jost / EcoMinga.

IMG – El río Anzu – Lou Jost / EcoMinga

A primera vista, la textura de esta flor de orquídea zapatilla de dama no tiene nada de especial. Se ve suave como cualquier otra flor. Nunca le había dado una segunda mirada hasta ese día. Un microscopio reveló que la flor fue un complejo mosaico de texturas, pelos, glándulas y cosas que todavía no entiendo. Los pelos fueron claramente guías para los polinizadores de insectos, los cuales primero deben aterrizar en el borde plano blanco de la bolsa o “zapatilla” de la orquídea (la bolsa se llama “labio” en la terminología de la orquídea). Este borde blanco tiene una fila de manchas verdes aleatorias y otra fila poco organizada de manchas marrones más grandes. Cuando se magnifica, los puntos verdes resultan ser muchas crestas largas paralelas de color verde oscuro, separadas por “valles” de color marrón verdoso. El efecto es casi iridiscente. [Edición Diciembre 1: En respuesta a la pregunta de Lisa a continuación, investigué un poco y descubrí que el polinizador es una mosca hembra que cree que estas manchas verdes son en realidad pulgones, la presa de las larvas de mosca. La hembra aterriza en la flor para poner huevos entre los “Pulgones” y cae en la bolsa. Mis especulaciones sobre las manchas que parecían ojos de mosca estaban equivocadas.

IMG – Vista superior de la “zapatilla” o labio de la orquídea Phragmipedium pearcei zapatilla de dama. Fotografía: Lou Jost / EcoMinga

IMG – El estaminoideo sobre la “zapatilla” o el labio. Con este aumento, las manchas verdes del labio comienzan a mostrar su verdadera complejidad. Fotografía: Lou Jost / EcoMinga

IMG – Con un aumento mayor, las manchas verdes del labio revelan texturas complejas y pelos rígidos. Fotografía: Lou Jost / EcoMinga.

IMG – Detalles de superficie notablemente complejos de las manchas verdes. Fotografía: Lou Jost / EcoMinga

IMG – Vista cercana de las manchas verdes revela que no son solo manchas suaves de color. Fotografía: Lou Jost / EcoMinga.

Eventualmente el polinizador debe caer dentro de la bolsa (quizás drogado por la orquídea). Una vez que el polinizador ingresa a la bolsa, se encuentra atrapado, con salidas limitadas. La mayor parte de la superficie interna del labio tiene solo un poco de vello, pero una de las tiras está alfombrada con pelos largos, y esta tira lleva al insecto hasta una ruta de escape que pasa directamente debajo del estigma y las anteras. Por tanto, el insecto se ve obligado a polinizar la flor si quiere salir de allí.

IMG – Una vista en sección transversal de la “zapatilla”. Fotografía: Lou Jost/EcoMinga.

IMG – Vista en sección transversal más cercana. Tenga en cuenta los distintos tipos de pelos. Fotografía: Lou Jost / EcoMinga

La variedad de texturas en esta flor me hace querer mirar más de cerca otras flores. ¡Espere ver más microfotografías de estas aquí en el futuro!

IMG – Una araña saltadora me mira fotografiando los saltamontes. Fotografía: Lou Jost / EcoMinga

Lou Jost, Fundación EcoMinga

Traducción: Salomé Solórzano-Flores

References

Munn, C. A. 1986. Birds that ‘cry wolf.’ Nature 319: 143-145